Another shake-up is underway in what’s become one of the most crucial jobs in state government: the top information technology officer.

Chief information officers (CIOs) in five states—Arkansas, Delaware, Hawaii, Kansas and Texas—have left their jobs in the last four months or announced they soon will depart. More are likely to follow, as at least 10 governorships will change hands in January, including those in Arkansas, Hawaii and Texas.

CIOs direct the rare corner of state government that holds out the promise of greater efficiency, better service, cost savings and innovation. State computer systems process everything from tax returns to driver’s licenses to welfare cases, and contain the personal information of millions of citizens.

Related: In a Fickle Shift, Tech Titans Embrace the GOP

“Technology does hold great promise,” said Otto Doll, now CIO for the city of Minneapolis and a former president of the National Association of Chief Information Officers (NASCIO). “People have to be careful not to overstate it. But there are great opportunities for technology. And it’s often not really about technology, it’s about a better way for … (state government) to operate.”

States trail the private sector in harnessing information technology to deliver faster, better, more cost-efficient operations and customer service. Several factors prevent them from catching up, but one is that the many CIOs who come from the private sector often choose to return after completing a short stint in public service.

CIO = Career Is Over

Doll was CIO of South Dakota before going to Minneapolis. But his tenure was a rarity. He was in the job for 15 years, having been appointed and reappointed starting in 1996 by former Republican South Dakota governors Bill Janklow and successor Mike Rounds.

At the time, the joke was CIO meant “Career Is Over.” A state CIOs’ tenure then averaged 26 months. Today, it remains under three years, at 32 months.

Related: Google Spends More Than Any Other Tech Giant to Influence Congress

Having a new governor of the same party doesn’t guarantee reappointment. Current South Dakota Gov. Dennis Daugaard, also a Republican, chose to emphasize priorities different from his predecessors and brought in his own CIO, Doll said. Such a move also is natural, he said. “Nobody likes to ride the coattails of his predecessor.” And that’s true in the private sector, too, he said. A new CEO often wants his own CIO to push his priorities.

“We’re anticipating quite a bit of turnover,” Stu Davis, Ohio CIO and NASCIO president, said of this week’s elections. “I think any time you have a position tied to an administration (that’s elected), you are going to see that.”

But elections aren’t the only factors driving turnover. Delaware’s governorship wasn’t up for election this year. But James Sills, the state’s CIO the last five years, announced in August he was leaving to return to his “first love,” banking. He’s now CEO of Mechanics & Farmers Bank in Durham, North Carolina.

Sills said governors often attract CIOs from the private sector, where they often return for better pay or to take on new challenges, such as start-up ventures, after giving time to public service and achieving some goals for the state. Although turnover can be disruptive, Sills sees an upside. “It’s a healthy thing to bring in somebody new from time to time to challenge the status quo,” he said.

Related: Keystone Pipeline Debate Can End with New Tech

Other factors also prevent states from quickly adopting new technology and moving at the private sector’s innovative pace, Sills said. And it’s a challenge for state CIOs, regardless of how long they’re on the job.

Information technology is a huge, expensive and sometimes politically risky proposition—when it fails, as it did during the rollout of the federal government’s health insurance exchange website, the fallout can cost people their jobs. For states, investment in it often involves legislative signoffs and byzantine purchasing requirements not found in business. And applying it to new or different ways of operating often meets resistance from a bureaucratic culture reluctant to change, he said.

Faster Turnover in Cybersecurity

If there’s a state job with an even higher turnover rate than CIOs, it is chief information security officers, or CISOs. They’re the people who police against cyberattacks on state databases and react to breaches.

Half the states have new CISOs compared to two years ago, according to a report last month from the consulting firm Deloitte & Touche LLP and NASCIO. And half the ones in the jobs two years ago were new compared to two years before that. The main reason for the rapid turnover: money. CISOs can make $250,000 to $500,000 a year in the private sector, said Srini Subramanian, a state cybersecurity specialist with Deloitte who co-authored the report. That’s far more than state governments can pay.

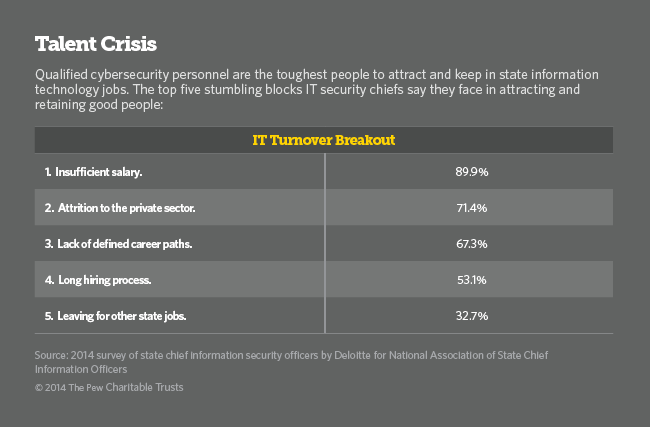

It’s a crucial job because state databases are under constant attack by hackers trolling for people’s personal identities, as Stateline has reported. And it’s harder to fill than the CIO post, Subramanian said. Even when a state has a CISO, that person struggles to attract and retain a staff. Recruiting any information technology staffer is an ongoing challenge for states, but attracting cybersecurity professionals is even more difficult.

“The cybersecurity professional is in top demand in the private sector,” Subramanian said. “So it takes the government all the more effort to attract qualified people to serve.”

In addition to the pay deficit compared to the private sector, state cybersecurity staffers are especially prone to burnout because they tend to work longer, harder hours than other information technology workers.

While states might offer better pay, clearer career paths and somewhat better benefits to attract and hold on to cybersecurity professionals, Subramanian said, there’s one trump card states have that the private sector doesn’t: the lure of public service.

It’s what attracted Davis, Doll and Sills to be state CIOs, they said, and why Doll said he stays in public service rather than returning to the private sector. “It’s not for the money,” he said. The chance to serve a community, give something back, help people or keep them safe, and maybe change lives is “about the only selling point,” Davis said. But, he said, it’s a good one. “It does get me out of bed every day.”

This article originally appeared in Stateline, a nonpartisan, nonprofit news service of the Pew Center on the States that provides daily reporting and analysis on trends in state policy.