The world will spend today mourning Nelson Mandela – and rightly so. With his death, we have lost one of those all-too-rare individuals: someone who is able to put justifiable grievances, anger and preconceived ideas to one side in the pursuit of the interest of society and social justice.

Part of his legacy will remain with us in an unusual form. His decision – and that of others heroes of the South African campaign to dismantle that country’s oppressive apartheid regime in favor of a truly democratic society – to choose passive resistance over violence helped pave the way for a new kind of investment strategy.

It was in the midst of this struggle that pioneers began to craft the philosophical underpinnings and strategic approaches for a new approach to investing that would become known worldwide as socially responsible or ethical investing. Today, hundreds of mutual funds and exchange-traded funds use some kind of screen to ensure that their portfolios don’t include stocks or bonds to which their investors are philosophically opposed to owning.

Amy Domini, one of that early group of socially responsible investors, was working as a stock broker when the South African divestment movement cranked into high gear at college campuses around the world. Already, she told me recently, she had begun customizing individual client portfolios to exclude tobacco stocks for families who had lost a relative to cancer, or shares in companies involved in weapons manufacturing for some Vietnam veterans.

It was the South African divestment campaign – and Mandela’s later acknowledgment that he believed it was a key factor in bringing the country’s white rulers to the negotiating table – that turned this from an occasional pastime into a lifelong passion, Domini said: “I realized that I might make a difference to a system that I deplored by simply refusing to participate in it with my money – and then Mandela validated my view by confirming that this had worked.”

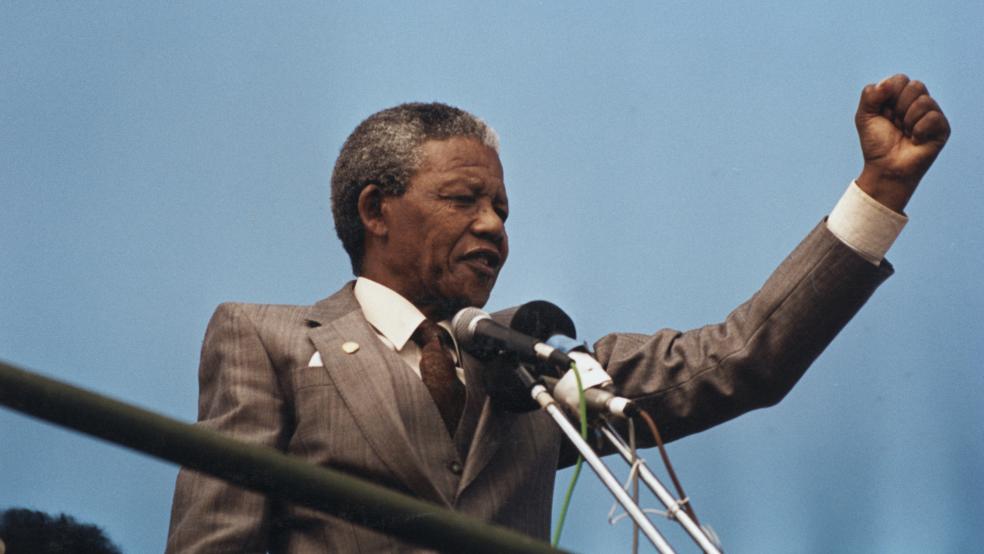

Related: Nelson Mandela – A Life in Pictures

Domini went on to create a socially responsible stock index, a family of mutual funds and now is moving on to build a new kind of investment vehicle, one that will focus not on excluding companies doing “wrong” but investing in those that are particularly constructive or progressive.

Mutual funds and ETFs dedicated to socially responsible investing strategies of all kinds now oversee some $120 billion, and institutional portfolios represent tens of billions of dollars more. And yet, the arena remains controversial.

First, there’s the idea that what is a sin to one individual is greeted with a shrug of the shoulders and a bemused look by his neighbor. Some funds don’t invest in weapons stocks or fossil fuel companies; others go so far as to shun stocks of companies they believe don’t pay high enough wages to their employees. (They’re putting their money to work to protest the same kinds of wage levels that many others have been speaking or marching about at Wal-Mart and fast food retailers in recent months.) For some, it’s enough to simply avoid those “sin stocks”; others want to seek out companies that are devoting their R&D budgets to green energy or GMO-free foods.

Broadly based funds are often the most useful choice for investors who want to ensure their portfolios remain diversified and well balanced. And yet, given that many managers of these ethical funds have different criteria for including or rejecting portfolio companies, investors can end up owning stocks that don't pass their personal tests to qualify as “acceptable” investments.

Avoiding defense and energy stocks probably has left many investors lagging the broad market for multi-year periods, especially in the middle of the last decade when military spending and crude oil prices were booming. At the same time, some (if not all) ethical funds can be slightly more costly in terms of management fees, reflecting the higher degree of research required on the part of fund company.

Clearly, the socially responsible investment industry is a significant part of Mandela’s legacy on Wall Street. What may be more important than the institutionalization of this investment strategy is the mindset behind it: that we can use our money to pursue our convictions about what is right and wrong, and even to change the world for the better.

Nor do we have to buy a specific kind of mutual fund to do so. It can be as simple as choosing to invest in a basket of stocks that doesn’t include businesses that conduct tests on animals, or that looks for those with a low carbon footprint. Social responsibility doesn’t even have to be defined in terms of a company’s business operations, but can be extended to include whether or not its governance passes muster.

Mandela’s activist legacy lives on at college campuses, where a new kind of divestment campaign – revolving around demands that university endowments pull their money out of oil and gas companies – is gaining strength.

It’s a legacy of constructive engagement and activism that needs to be honored and cherished, even if you don’t happen to share the specific convictions driving a particular activist. That’s one of the ways we can continue to honor Mandela’s positive contributions to the world we now inhabit.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: