When you get the bill for your emergency room visit, the sticker shock might make you sick enough to go back there.

A study last week by the University of California San Francisco puts emergency room prices in the spotlight, and finds that not only do prices vary greatly, but no one—patients nor doctors—seem to know how much a procedure will cost or the reasoning behind its price tag.

RELATED: 5 Health Care Reform Changes Coming in 2013

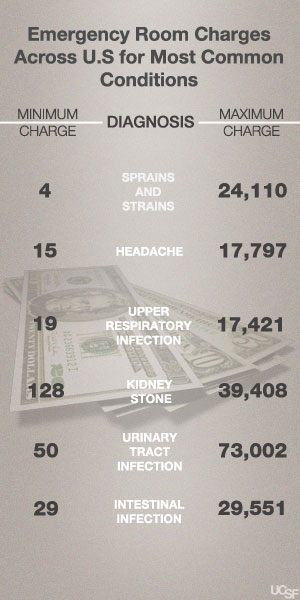

When you visit the emergency room, you could be charged anywhere from the cost of a cup of coffee—to the cost of a new Porsche. Researchers looked at costs for diagnosing the 10 most common conditions among 8,303 emergency room patients across the country, and found as much as a $72,952 difference for the same diagnosis. Bills to patients or insurers ranged from $4 to $24,110 for sprains and strains; $15 to $17,797 for headaches; $128 to $39,408 for kidney stones; $29 to $29,551 for intestinal infections; and $50 to $73,002 for urinary tract infections.

Nearly half of the patients in the study had private insurance, while the remaining had either Medicaid coverage or were uninsured. The researchers excluded Medicare patients 65 and older, and they wanted to focus on adults age 18-64 who are at the highest risk of facing large out-of-pocket charges on their bills. The median total bill for outpatient conditions was $1,233. Medicaid patients were charged the highest median price at $1,305, followed by those with private insurance ($1,245), and uninsured patients ($1,178), though the uninsured are expected to pay the bill in full.

“Patients actually have very little knowledge about the costs of emergency visits that may or may not be partially covered by insurance,’’ says Renee Hsia, M.D., senior author of the study and assistant professor of emergency medicine at UCSF in a statement. “Much of this information is far too difficult to obtain.’’

The study comes on the heels of a cover story in TIME Magazine titled Bitter Pill: Why Medical Bills Are Killing Us that investigates the numbers behind hospital bills. Author Steven Brill writes “When you look behind the bills that patients receive, you see nothing rational—no rhyme or reason—about the costs they faced in a marketplace they enter through no choice of their own. The only constant is the sticker shock for the patients who are asked to pay.”

While patients and doctors remain confused about hospital charges, emergency room visits in the U.S. increased 43 percent between 1997 and 2008, according to a 2009 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report, the latest data available. A 2011 survey from the American College of Emergency Physicians also found that emergency physicians are seeing more Medicaid patients who could not find primary care doctors to accept their health insurance. Nearly 90 percent of emergency physicians expect to see an increase in ER visits when the Affordable Care Act is implemented.

Though the UCSF study did not identify which emergency rooms had which prices, Hsia notes that county hospitals tend to be the least expensive and for-profit hospitals charge the most. Competition also matters. If there is only one hospital chain in the area and no competitors, prices tend to be higher overall. Trauma centers and teaching hospitals also tend to have higher chargers. Part of the wide variation in price is also due to how the condition is treated. Someone may come to the ER with a splitting headache, and may require a CAT scan and maybe even a lumbar puncture to rule out a brain hemorrhage, which helps explain the high end charges for a diagnosis that ends up being a headache. The price of that CAT scan, however, varies widely from hospital to hospital.

The main problem, according to Hsia and Brill, is that there is no consistent guide for what price should be charged, with every hospital having their own system for determining prices. Hospitals have something called chargemasters, or price lists that are maintained by the hospital, but no two price lists are the same. Hospitals often grossly exaggerate the prices because they negotiate them with insurers, who often only pay a small percentage of each charge. The exaggerated list price is not intended to be paid in full, yet thousands of uninsured see the list price show up on their final bill. Insured patients also feel the pain, since they’ll see these higher prices reflected in premiums, and those who have high deductibles, limited coverage, or receive out-of-network care are often asked to pay full price.

The health care system needs a more streamlined approach of pricing, says Hsia, like a baseline cost list for treating all conditions that could be determined by a consensus of providers and insurers. Since hospitals typically have higher costs, they could say they are going to charge X times this amount of the baseline costs, or they could charge more if they provide higher quality, explains Hsia. The numbers should then be made publicly available. “This at least would make for a more rational system than we currently have, and starts to address the cost issue that health care reform has so far fundamentally been unable to address,” she says.