State of the Union speeches weren’t always national events.

For much of our history, they were just written reports to Congress, rather than hour-long addresses interrupted by bursts of clapping and TV cameras panning the audience inside the House chamber for smiles and scowls.

President Obama faces a tall order tonight as he talks about the economy, the federal budget, gun control, climate change, and a slew of foreign policy concerns.

He rose to prominence for his oratorical skills, yet the State of the Union is commonly seen as a laundry list of past achievements and future plans. No matter how dire the circumstances, the State of the Union is always strong enough to withstand the worst possible disaster.

“Think of the state of the union more as a blunt instrument than an object of precision,” said Adam Lawrence, a political scientist at Millersville University in Pennsylvania whose analysis of past speeches was cited recently by the Congressional Research Service.

Thomas Jefferson—who saw the constitutional requirement to update Congress as monarchical—first started submitting them as written messages in 1801. James Monroe deployed his 1823 report to say the United States would intervene if European nations attempted to further colonize North and South America, a policy now known as the Monroe Doctrine.

The “Annual Message to Congress” as it was known before World War II became a speech again in 1913, when Woodrow Wilson successfully pressured lawmakers into establishing the Federal Reserve. But speeches were delivered infrequently until Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s tenure, when the words “we” and “our” appeared with more frequency.

With that in mind, here is what history tells us to watch for this evening when Obama takes the podium:

TV Changed Everything – Lyndon B. Johnson coined the phrase “war on poverty” in his 1964 State of the Union, yet his real revolution involved scheduling his speech the next year at 9 p.m.

Previous addresses were delivered mid-day when most of the country was working. The later time drew a bigger audience, and—even if ratings are slipping—the later time slot is a chance for the president to command an hour of the public’s time without a filter. Slight changes in the medium by which the speech is delivered or watched have an impact on its reception. So monitor the Twitter feeds.

“Generally speaking, Johnson was the most successful in getting his requests enacted,” said Donna Hoffman, a political scientist at the University of Northern Iowa who has measured how often goals from State of the Union goals translated into policy. “He was pretty savvy in recognizing the potential of the speech.”

Of course, Johnson’s innovation led to the start of another time-honored tradition—the opposition response. Future president Gerald Ford, then a Michigan congressman, and Illinois Sen. Everett Dirksen delivered the first response for the GOP in 1966.

It’s Only A Wish List – Just 43.3 percent of the proposals included in State of the Union addresses between 1965 and 2002 were enacted that legislative session, according to analysis by Donna Hoffman and Alison Howard of the Dominican University of California.

That average drops for second-term addresses and in divided governments. Hoffman and Howard updated their research for Obama and found his success rate was 47.6 percent for his first three years in office, but it plunged to 11.9 percent for the first six months of 2012.

There are a host of other factors that determine the fate of legislation and the presidential election certainly didn’t help Obama much last year.

Check When Republicans Applaud – It’s easy for Obama to bring Democrats to their feet, as GOP lawmakers have recently sat on their hands.

But it’s exactly when Obama elicits a standing ovation from everyone that his ideas have a chance of becoming law, said Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania. You can predict the chances for his agenda by how Republicans react—and lines like “You Lie!” from Rep. Joe Wilson, R-SC., in 2010 are an awful sign.

No one mastered the applause lines quite like Reagan, who used his gift for storytelling to bring the then-Democratic House majority to thunderous applause.

“Ronald Reagan would use an evocative narrative,” Jamieson said. “Both sides would stand and applaud and while both sides were on their feet, he would add a controversial policy.” The TV cameras would catch the Democrats still clapping as Reagan sneaked in his legislative ideas.

Celebrity Guests – Reagan pioneered another hallmark of the State of the Union: a guest celebrity watching the speech from the gallery with the first lady. The first invitee in 1982 was Lenny Skutnik, who weeks earlier jumped into the Potomac River to rescue an airplane crash victim.

The guest often personifies a principle contained in the speech.

For example, sharing Michelle Obama’s seating area last year was Debbie Bosanek, better known as Warren Buffett’s secretary. The billionaire investor complained that he paid a lower tax rate than Bosanek—a difference that Obama pledged to end.

This time around, the focus is on gun violence—with the parents of Hidaya Pendleton, a 15-year old high school student killed last month in Chicago, reportedly watching the speech.

But not every guest proves a success.

Chicago Cubs slugger Sammy Sosa attended the speech in 1999 with Hillary Clinton, only to be shunned from the Hall of Fame years later for his alleged use of performance enhancing drugs.

Less is Usually More – When the State of the Union was still a written report, it could last for 25,000 words. The most recent Obama addresses were roughly 7,000 words.

Past studies suggest it’s worth not loading up the speech with policy proposals, since they tend to dilute the overall message and get lost in the shuffle. The median level of proposals in past addresses was 31, with extremes coming from Jimmy Carter in 1980—just 9 policy requests—and Bill Clinton in 2000—a whopping 87 requests.

“The more issues a president talked about, the less effective he was,” said Millersville University’s Lawrence. “That’s stupid from an impact point.”

Quantity Beats Quality – It’s not about soaring rhetoric on Tuesday night, but how many words Obama devotes to a particular subject.

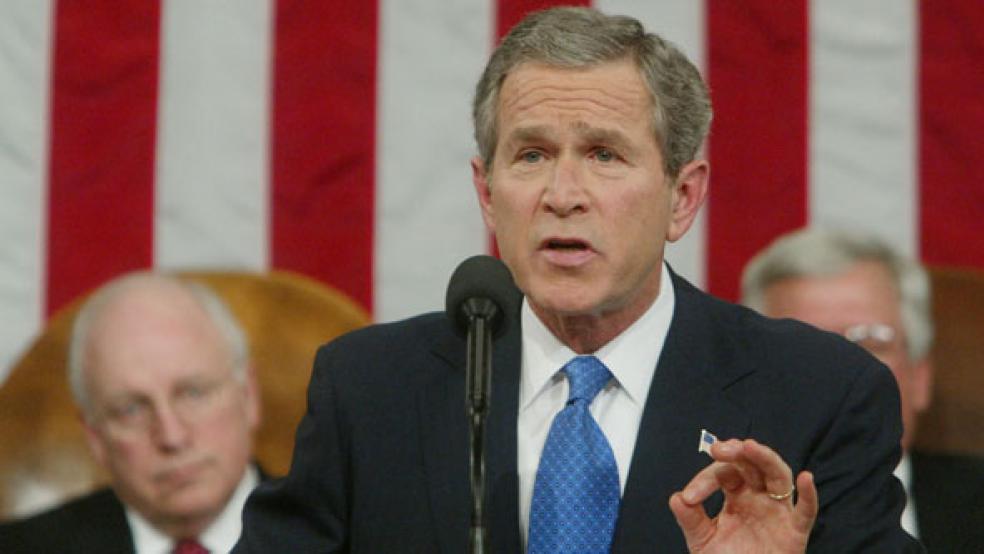

George W. Bush used the name “Saddam Hussein” 19 times in his 2003 address.

For every 50 words a president devotes to an issue, there is a two-percentage point increase in the public saying that problem is the most important in the country, according to Lawrence’s research.

Bush used his State of the Union to call for an invasion of Iraq. And while everyone remembers his unique turns of phrase such as “Axis of Evil,” his repetition in making the case matter just as much.

“He was able to promulgate these ideas,” Lawrence said, “and the American people bought it hook, line and sinker.”