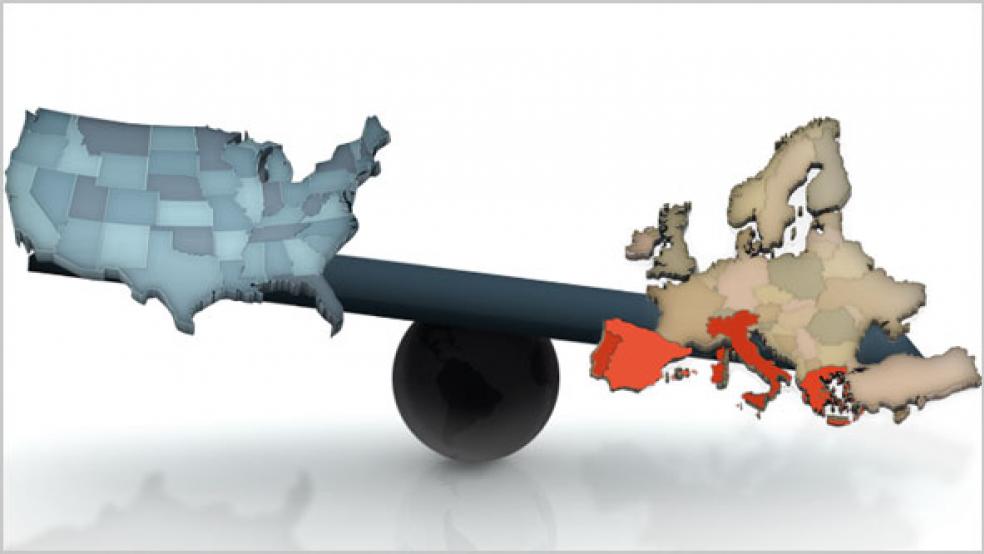

The European Union, the world’s largest single market representing more than 30 percent of global GDP, is likely to face recession in the coming year, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). In late November, the Paris-based think tank forecast that the eurozone economy, comprising 17 of the European Union’s 27 members, will decline 1 percent in the fourth quarter and another 0.4 percent in the first quarter of next year. Meanwhile, the United Kingdom’s economy is expected to contract 0.03 percent and then 0.15 percent.

Largely as a result of the problems in Europe, the OECD projects that global growth will drop from 3.8 percent this year to 3.4 percent in 2012. While global trade is expected to rise 6.7 percent by the end of this year, the OECD predicts trade growth to decline to 4.8 percent during 2012.

Wharton management professor Mauro Guillen says the European debt crisis and looming economic contraction will be key factors behind any slowdown of trade. With Europe having less money to spend, demand for exports from around the globe will fall. “Europe is a big market for everybody,” he notes, adding that it accounts for as much as 50 percent of revenues for some U.S. multinationals.

Beyond the impact on global trade, Guillen warns that the difficulties in Europe could lead to new instability in the international financial system that would restrict access to credit and choke growth. He points out that J.P. Morgan Chase and Goldman Sachs recently disclosed to shareholders that they have sold derivatives covering more than $5 trillion of global debt. However, the two financial institutions have not identified how much of that amount has been issued by European countries with sovereign debt problems, such as Greece, Italy and Spain. “It is likely that some chunk of that is European debt,” he notes. “So it’s not a good thing, for sure.”

Wharton finance professor Franklin Allen is also worried about a European banking crisis triggering new tumult in financial sectors around the world, including the U.S. Concern is already reaching levels last seen in 2008, when Lehman Brothers collapsed and the global financial crisis began. “There has just not been a Lehman-type event. But if a big bank like UniCredit [in Italy] or BNP Paribas or Société Générale [of France] were to go, this would be a big problem.”

‘Quite Slow Growth’

Politicians in the troubled eurozone have announced steps to work together to put an end to the crisis, and hopes are high for the fiscal agreement that policy makers are expected to unveil following the current crisis talks in Paris and an EU summit in Brussels. However, according to Allen, each time a new plan is announced, political leaders concede that it will be complex and difficult to reach an accord between every eurozone member and implement a successful pan-Europe recovery plan.

While the potential fallout of a European recession on U.S. exports is less of a concern than a banking crisis, it will still have an impact. Howard Pack, Wharton professor of business and public policy, says that a decline in European demand will be a blow because the recovery underway in the United States is so fragile. “U.S. growth is expanding slowly, and export growth could be important to keep the country growing,” Pack says. Allen agrees that a recession in Europe will turn what has been expected to be slow to moderate growth in the U.S. into “quite slow growth.”

According to Pack, the economic woes in Europe could drive down the value of the euro, which would make it harder for U.S. manufacturers to sell goods in Europe because their products would be relatively more expensive than those made in the EU. On the other hand, he notes, U.S. equity markets could attract new investment from European investors worried about economic weakness at home.

A report released by asset management firm AllianceBernstein in November indicates that a fall-off in exports to Europe would harm the U.S. economy, but would not be devastating. The report notes that the share of U.S. goods exported to Europe has dropped from 19 percent in the early 1990s to 13 percent today. Even a 10-percent reduction in imports to Europe would result in a cut in U.S. production by only 0.2 percent, the report states.

China: A Real Impact

Since the 2008 collapse of Lehman Brothers triggered the global financial crisis, much of the hope for global economic growth and recovery has focused on China. Now, however, even China is not as buoyant as it has been, and a European recession could put a damper on the Chinese economy with damaging ripples through global markets.

Marshall Meyer, Wharton management professor, observes that while the greatest threat of a European recession to the United States economy would be financial contagion through the banking system, Chinese state-controlled banking giants “are not going to be dented” by debt problems in Europe. Rather, the impact of a recession would be on China’s real economy.

A slow- or no-growth European Union – China’s largest trading partner – would diminish Chinese exports, which might result in factory closings and job losses in the country. Meyer cites shipping cost figures from Clarkson Securities, a London-based brokerage services firm for the shipping sector, that suggest demand in Europe is already substantially weaker than, say, in the U.S. From September through November, the price of shipping goods from China to Europe fell 39 percent, compared with 18 percent from China to the United States.

A big drop in employment in China, he warns, could trigger protests and social unrest, something that officials in Beijing have long been wary of. “The greatest concern of the Chinese economy is not the financial economy. It is always the state of mind of the workers,” Meyer contends. The government doesn’t “want any incidents of mass unrest in China, and recent numbers show that unrest has increased dramatically.”

According to Meyer, the crisis in Europe heightens the need for China to wean itself off its export-driven, fixed asset-based economic model by encouraging more corporate and consumer spending at home. Yet, he notes, China is a nation of savers, and until the government’s embryonic reforms of the national social safety net take hold, the Chinese are unlikely to change soon. More spending domestically might also help stimulate Chinese industry to be more innovative and develop new products, rather than focusing on producing high volume, low-value goods, he adds.

It is difficult to say what policy paths China will take because of next year's changeover of leadership in Beijing. “The prediction is that the current government will muddle through for the next year,” says Meyer. “After that? Nobody knows.”

The Least to Lose

As for the rest of the world, Allen suggests that India has the least to lose from a European recession. Like China, growth prospects for India’s economy are more encouraging than elsewhere, mainly because it is relatively independent of other parts of the world, including Europe.

Meanwhile, Pack notes that commodity-producing nations of South America and Africa may not ship directly to Europe, but will be hurt by slowing demand from Chinese manufacturers as a result of the European recession.

Closer to home for the EU, Guillen says Russia and other Central and Eastern European nations that are not part of the eurozone are highly reliant on their neighbors to the West and will be harmed by lower exports of gasoline and commodities.

Others agree. The deepening eurozone turmoil “is likely to drag large parts of emerging Europe into recession over the next year,” according to a December 7 research note from Capital Economics, a London-based research house, citing not only a drop in trade, but also weaker capital inflows and banking sector fall-out. “Financial sector vulnerabilities mean that recession risks are greatest in Hungary, Ukraine and the Balkans – indeed, in the extreme, IMF assistance may ultimately be needed to avert an external financing crisis in all of these economies.”

Within the eurozone, the recession’s impact will reverberate across borders. “For countries on the periphery, particularly Greece and Portugal, it is very bad news,” Allen contends. “It will accentuate their problems. I think it is not good for Italy or Spain.” Even the French and German economies will suffer as recession slides across the continent, he adds.

Growing Impatience

In early December, markets rallied when the U.S. Federal Reserve began working with the European Central Bank, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan and Swiss National Bank to pump money into European banks. Guillen says such coordinated action by the central bankers indicate growing impatience with politicians and their inability to resolve the eurozone’s sovereign debt problems.

As he sees it, Europe’s debt woes are a continuation of the crisis that struck the U.S. acutely in 2008. However, because the global recovery has been weaker than anticipated, governments are under heightened pressure to manage economies that are deeply in debt and facing tax shortfalls due to unemployment and other downturn-related factors. In many countries, that may mean a wave of new austerity measures.

The concern about a recession “is aggravating everything,” says Guillen. “It is dynamic and becomes self-reinforcing. My sense is that people's expectations about the [financial] future ... are quite low.”

He notes that even a bit of news about moving toward a resolution of the sovereign debt issues in Europe tends to create a small rally in financial markets, but that seems to disappear quickly when new obstacles arise. “People are so pessimistic, but the underlying problems are the politicians in Europe and the U.S., and Japan,” Guillen notes. “They need to get their act together and stop dragging their feet with partial solutions.”

According to Guillen, an ideal way to address the European financial situation would be to roll out austerity programs while being mindful of any downward turns in business cycles. And healthier major economies, like Germany or China, could continue to spend while debt-laden economies work their way through the programs.

But the problem is a paradox, Guillen notes. Cutting back spending in the short term will reduce debt but make the recession worse and further aggravate long-term economic woes. “It would be better to implement policies that would achieve fiscal balance and reduce budget deficits in five to 10 years.” But in the next year or two, the focus should be on providing fiscal stimulus to stabilize weak national economies and troubled banking systems. “Once the economy starts to grow, it will be easier,” Guillen predicts. “Trying to accomplish everything in the short run is not only hard, it's self-defeating.”

Pack says there is much uncertainty since it is not clear how severe Europe’s recession will be. In general, since World War II, recessions have resulted in a decline of between 3 percent and 5 percent of a country’s GDP. Most of those recessions, however, were induced by governments trying to curtail inflation. “In a scenario like today’s, when we’re not sure of the financial health of the banks and there’s going to be huge cutbacks in government spending, the precise magnitude” of the recession’s impact is hard to predict.

Republished with permission from Knowledge@Wharton, the online research and business analysis journal of the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.