Most investors have been distracted in recent days by Friday's payroll report (and what it means for the Federal Reserve's rate hike schedule) and the ongoing Cold War standoff between Greece and the European establishment, but the really big news is what's happening over in China.

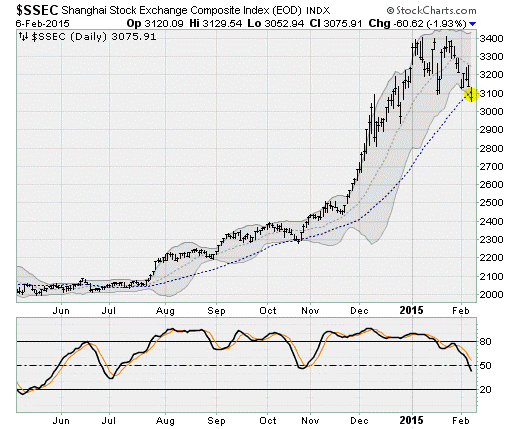

Since last summer, the Shanghai Stock Exchange Composite Index has been melting higher, rising more than 60 percent into a triple-top pattern in January. The move has been driven by anticipation that Beijing would acquiesce by cutting interest rates and unleashing stimulus in response to an ongoing economic slowdown.

Related: The ECB Just Got Tough with Greece, and Investors Should Be Worried

In November, the People's Bank of China kicked things off by cutting its policy rate for the first time in more than two years. On Thursday, the PBoC cut its Bank Reserve Ratio by 0.5 percent to 19.5 percent — reducing the amount of capital reserves Chinese banks must hold — in the first broad rate cut since May 2012. According to the Australia & New Zealand Banking Group, this is poised to free up as much as $96 billion.

Yet Chinese stocks crashed through their 50-day moving average in a way that hasn't been seen since last June, putting the recent uptrend at risk of reversal.

The problem is that Beijing has since indicated that the move is not the start of a broader credit easing cycle, but instead was a targeted action designed to relieve some of the pressure within China's financial system. Combined with recent action to cool stock market gains (via crackdowns on stock margin lending) the overall message is that policymakers seem committed to a regime of tough, deleveraging medicine even as GDP growth slowed in 2014 to 7.4 percent — the slowest rate in the last 24 years.

In a front-page editorial in the Economic Information Daily, Xu Gao, a well-known Chinese economist, argued that tight monetary conditions were not causing China's economic problems and that aggressive easing could exacerbate the actual problems of overcapacity and other factors in the long run. Moreover, officials from China's National Development and Reform Commission have repeatedly said that no major stimulus measures were in the pipeline.

Related: The Bond Market Is Warning of Huge Trouble Ahead

Even the People’s Bank of China has been dismissive of the November rate cut, saying it was done to offset passive tightening caused by falling inflation rather than as an outright easing measure.

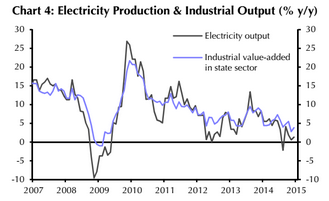

It's a tough balancing act because the Chinese economy is clearly hurting. The official Purchasing Managers' Index measure of factory activity in China contracted on a monthly basis in January for the first time in two years. Chinese industrial profits plunged by the most in at least three years in January, down 8 percent on a year-over-year basis. Profits in coal mining dropped 46.2 percent in 2014. Oil processing and nuclear fuel profits dropped more than 79 percent. The chart below, from Capital Economics, shows the slowdown in electricity production, a proxy for overall economic activity.

Louis Kuijs, chief China economist at the Royal Bank of Scotland, is looking for Chinese GDP growth to slow to 7.0 percent this year, well below the official 7.5 percent target. Deflation is also a problem, with producer prices falling at a 3.3 percent year-over-year rate in December due to overcapacity and lower commodity prices.

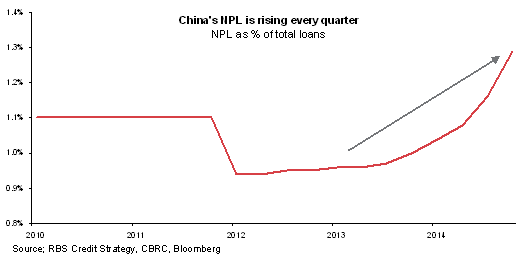

The stakes here couldn't be higher. The head of China's Dagong Ratings Agency recently warned that we may face a "new world financial crisis in the next few years," with the situation more vulnerable than it was in 2008. Falling profits and prices are combining with recent interest rate increases to pinch borrowers, many of whom are simply unable to service their debts. Non-performing loans are on the rise in what looks like the start of a possible credit crunch.

Credit growth has been mind boggling, making the situation more dangerous than many realize. China's total debt (including debt of the financial sector) has nearly quadrupled from 2007 through the middle of 2014 to $28.2 trillion, according to new research by the McKinsey Global Institute. That's equivalent to 282 percent of GDP, higher than the debt-to-GDP ratio for the U.S., Canada or Germany. At its current pace, China's debt burden would equal Spain's at 400 percent of GDP by 2018.

Related: The Stock Market Is Weaker Than It Looks

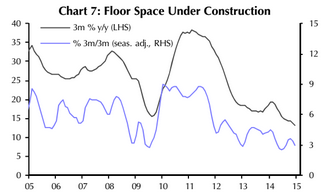

Much of this is connected to the real estate market, which by one measure of activity — floor space under construction — has fallen below 2009 lows. Real estate transaction volumes are down around 10 percent across China and unsold inventories are accumulating. In smaller inland cities, inventory stands at upwards of 77 months of sales. For the country overall it's near 18 months. In the U.S., it's 5.8 months. (As an aside, real estate is responsible for 15 percent of Chinese GDP while land sales make up 25 percent of local government revenue. The problem will be manifold should the slowdown continue.)

And a good chunk of debt is held outside the formal banking system in various trust and wealth management products, as well as commodity-backed financing deals, which have been rattled in recent years. In early 2014, the collapse of the "Credit Equals Gold #1" trust product focused attention on the issue. More recently, a swift drop in copper prices has put various cash-for-commodity loans on the rocks.

Complicating matters has been the drop in export competitiveness by Chinese factories. The Chinese yuan tracks the U.S. dollar, which has been surging as the Japanese have vigorously devalued the yen while the euro has dropped on fears of a Greek exit from the Eurozone.

Given the size and complexity of the issues China faces, the shenanigans on the Shanghai exchange over the last seven months looks like a last gasp of credit-based enthusiasm before the realities of deleveraging set in.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times:

- How Wall Street Is Fighting to Rip Off Your Retirement Money

- Is the Unemployment Rate of 5.7 Percent Just a ‘Big Lie’?

- Putin Risks It All on Korean Nukes and Cheap Vodka