What defines the “American dream” and American exceptionalism better than entrepreneurship? In ages past, birth determined a person’s station in life, and usually a very narrow set of career choices. In America, though, one could build the proverbial better mousetrap and eventually own a mousetrap-manufacturing business.

That sense of innovative entrepreneurship provided social mobility in America more than in any of the Old World countries; it broke down class structures, and forced larger businesses to compete in the marketplace. Not only did this provide the best benefit to consumers, but the entrepreneurial environment also provided a rapid improvement in the standard of living in the US, even for lower-income families.

For generations, economic liberty and dynamism defined America and set us apart from the rest of the world. Now, if a new study from the Brookings Institution is right, it’s fading rapidly into a memory.

Related: Why a ‘Too Big to Manage’ Government Should Downsize

“Business dynamism is inherently disruptive,” write Ian Hathaway and Robert Litan, “but it is also critical to long-run economic growth.” Business dynamism refers to the birth and death rates of private-sector firms. Historically, the US has seen a ratio that strongly favors new businesses over business failures, in a process that parallels the concept of creative destruction in the marketplace.

Put simply, business failures enable resources to be unlocked for the use of more efficient and successful businesses. The study refers to this as “churn,” and it forces capital, labor, and resources to better uses.

Historically, this form of creative destruction has produced a higher rate of business “births” than business “deaths,” to use the terminology of Hathaway and Litan. This makes sense, both in the theoretical sense and from our own sense of American culture. The natural flow of free markets should bring fresh capital and resources to entrepreneurs, and the expansive nature of those interactions should mean an increasing amount of those resources for utilization.

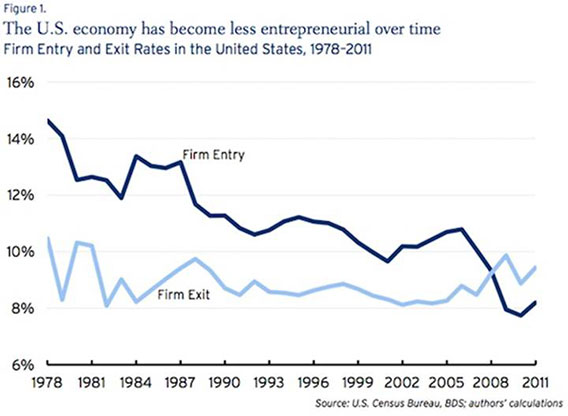

However, over the last thirty-five years, the ratio slowly dwindled, and eventually reversed itself. Tracking business births and deaths since 1978, this chart shows that business dynamism has been in serious decline, especially in the business birth rate metric:

The dramatic plunge in business births took place during the Great Recession, which will come as no surprise to any business owner or investor who endured that period. This chart from Hathaway and Litan shows that business births have been declining as a percentage of the economy since the 1970s. Except for a brief resurgence during the Ronald Reagan era and a much smaller and shallower improvement under George W. Bush, the rate of business births deteriorated at an even pace – even though the rate of business deaths held almost steady.

Related: Government Blatantly Wastes $30 Billion This Year

What happened? Hathaway and Litan shrug their shoulders after finding that these trends held steady across all states and metropolitan areas. Clearly, “business dynamism and entrepreneurship are experiencing a troubling secular decline,” they conclude, but “our findings stop short of demonstrating why these trends are occurring, and perhaps more importantly, what can be done about it.”

However, the chart itself suggests one answer in particular. The decades involved in this study saw a significant and accelerating expansion of federal regulatory power, which only had one period of significant reversal – the Reagan era. That period shows the only significant return to a higher rate of business births in the last thirty-five years.

The consistency of the decline across regions and states also bolsters this interpretation. Some states and regions have better economic growth rates than others; Texas Governor Rick Perry has recruited major employers from California on that basis, most recently Toyota’s US headquarters and its 5,000 jobs. Despite a friendlier tax and economic climate, though, Texas still has a lower business birth rate than it did thirty years ago, and so does every other state, and every metropolitan area save one (unnamed).

The problem, therefore, is national, and must relate to regulatory or tax policy or a combination of both. During this period, though, taxes didn’t increase sharply for businesses, at least not until recently. With few and temporary exceptions, though, the federal regulatory regime has only increased. The Phoenix Center pointed out this implacable escalation in its April 2011 policy bulletin on regulatory expenditures.

Related: Why the Bloated U.S. Government is Too Big to Succeed

As a share of private sector GDP, the federal regulatory burden has increased over the same period as this study. The Phoenix Center recommended at the time that even a small decrease in federal regulatory burden – just 5 percent, roughly decreasing the regulatory budget by less than $3 billion – would generate an additional $75 billion in the economy and add 1.19 million new jobs to the private sector.

Instead, we passed Obamacare.

We have another indirect method to test this conclusion, too. Expanded regulation tends to favor larger and more established firms in a market, which have more resources and better economies of scale to deal with compliance issues. Sure enough, the Brookings Institution study found that kind of dynamism alive and well. “Whatever the reason,” the authors conclude, “older and larger businesses are doing better relative to younger and smaller ones.”

Whatever the reason … the core value of American economics is slowly dying off. As the Brookings chart shows, we have finally crossed over to an environment where there are fewer businesses being created than fail – and the latter is spiking upward despite the Obama-era “recovery.” Capital no longer meets up with entrepreneurs to innovate and expand. We have exchanged business dynamism for regulatory stagnation, and “creative destruction” for the slow death of the American dream.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: