|

In an economy beset by a housing crisis and unable to capitalize on low mortgage rates, efforts toward streamlining the refinancing process would seem to be a no-brainer. Refinancing reduces monthly payments, putting more money in people’s pockets, and it doesn’t cost Washington—or taxpayers—a dime. But in the current economic and political climate, the issues surrounding any government effort to assist mortgage refinancing are so thorny that any real progress will be difficult to achieve.

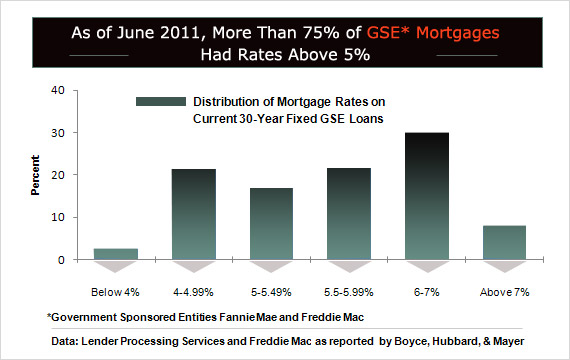

No one challenges the potential benefits of refi reform. Since 2008, mortgage rates have fallen more than 2 percentage points. Mortgage rates for 30-year fixed loans averaged 4.09 percent on Sept. 22, according to the weekly Freddie Mac survey, and new efforts announced last week by the Federal Reserve aimed at cutting long-term interest rates, including additional purchases of mortgage-backed securities, are sure to push them well below 4 percent. Refinancing a $200,000 mortgage from 6 percent to 4 percent would add about $250 per month to a homeowner’s cash flow. Studies show that the gross savings to homeowners could run from $50 billion to $70 billion. But that’s not happening.

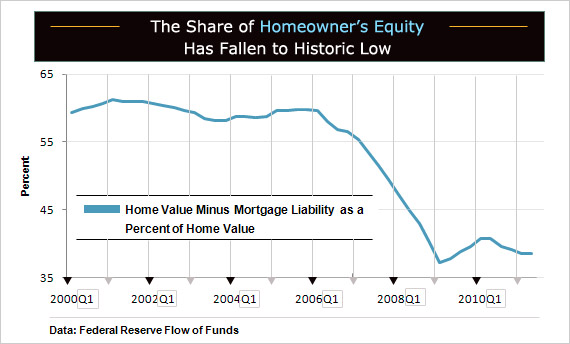

The poster child for the problem is the Home Affordable Refinancing Program (HARP). The program was launched in 2009 to allow low-equity and negative-equity homeowners who have loans guaranteed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and who are up-to-date on their payments to refinance their mortgages. Of the 4 million to 5 million homeowners the program was designed to help, those with loan-to-value ratios of 80-125 percent, only about 840,000 have used the program despite the lowest mortgage rates in 60 years. Only a small number of underwater homeowners, those with mortgages greater than their home’s value, have refinanced.

The program is not working because the objectives of the banks, Fannie and Freddie, and their regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), are at cross-purposes with the millions of homeowners HARP is designed to help. The FHFA’s mandate as the conservator of Fannie and Freddie, which were taken over by the government and bailed out in 2008, is to assure that these Government Sponsored Entities (GSEs) don’t lose any more money and begin to repay the billions they still owe taxpayers for their bailout. Current GSE rules force banks to uphold tighter standards and demand higher borrowing costs, rules that cannot be softened without heaping more risk on the GSEs—and taxpayers—and reducing the GSEs’ income.

Unlocking the potential of a program like HARP is getting increased attention in Washington. President Obama in his jobs speech on Sept. 8 said the administration is working with regulators to encourage more refinancing. Edward DeMarco, acting director of the FHFA, said on Sept. 19 that his agency is “carefully reviewing the mechanics of the HARP program to identify possible enhancements that would reduce barriers for borrowers already otherwise eligible to refinance using HARP.” Good luck with that, say most economists.

One of the biggest issues is so-called put-backs. Banks package their mortgage loans and sell them to Fannie and Freddie, which pool them into agency-guaranteed mortgage-backed securities. But Fannie and Freddie don’t have the resources, or the time, to review the details of each loan, so they demand an agreement, called a representation and warranty, requiring the bank to buy back the loan at full value if the borrower defaults and the mortgage shows a flaw in the underwriting. The bank then gets stuck with the bad loan, which can cost dearly. Analysts at Barclays Capital say that for every put-back, a bank has to make 35-50 clean loans just to break even. “Banks have sharply tightened mortgage credit in an effort to lower put-back risk,” says Barclay’s Ajay Rajadhyaksha.

Economists believe a full waiver of reps and warranties would be needed to make meaningful progress on refinancing, but few think that will happen. A waiver of would shift risk away from banks and onto the Fannie and Freddie, which are already on the hook to taxpayers. It would also cut the GSE’s income from put-backs and reduce returns when existing mortgage-backed securities are refinanced, which would result in lower-yielding securities. Tension between the FHFA and the banks is already high. The FHFA filed suits against 17 banks on Sept. 2 in an attempt to recoup money lost by the GSE’s on some $200 billion in risky mortgage investments—hardly an act that will encourage more refinancing.

Plus, even as HARP was established, Fannie and Freddie began to require additional interest rate charges from banks, called “loan-level price adjustments” for refi borrowers with high loan-to-value mortgages—directly counter to the aim of HARP—and low credit scores. Borrowers must have credit scores above 720 to qualify for the market rate. Moody’s Analytics economist Mark Zandi, who along with several other witnesses testified before a Senate subcommittee on mortgage refinance on Sept. 14, says that just over half of U.S. households score less than 720.

Other issues include the portability of mortgage insurance from one loan to another, currently not allowed, along with unnecessarily high closing costs and whether or not to extend HARP coverage to homeowners who owe more than 125 percent of the value of their homes. Data from CoreLogic for the second quarter show that 4.7 million of the 10.9 million underwater homeowners have loan-to-value ratios greater than 125 percent.

The last time mortgage rates dropped two percentage points, from 2000 to 2003, refinancing activity soared from an annualized rate of less than $1 trillion to more than $4 trillion. Moody’s Zandi says the current level of activity is less than half that, despite the millions of homeowners with above-market rates that could benefit from a lower rate. Zandi and other reform proponents say helping homeowners refinance who have already proven their ability to pay and are underwater only because of the plunge in home prices would actually reduce the number of defaults and not materially change the risks to the GSEs or taxpayers.

Critics disagree. They say reform steps needed to increase lending to risky underwater homeowners would likely increase losses for Fannie and Freddie. Refinancing mortgages with balances greater than 125 percent of a home’s value could not be securitized, they say, meaning that the GSEs would have to hold these risky loans on their balance sheets. And analysts say indemnifying banks against put-back risk just looks bad. “What the GSEs would be seen as doing is giving a free pass to banks that made bad loans, instead of penalizing them for it,” says Barclays’ Rajadhyaksha.

All this means that in the current Washington climate, any economic benefit of refi reform will have to stand the test of both economics and politics—which is a very high hurdle.