|

When it comes to job hunting, big is out. Small is in. Over the past decade, the explosion of global trade and a sharp focus on productivity and cost cutting have accelerated a key trend in U.S. labor markets: Jobs at big companies just aren’t as plentiful as they used to be. That means the burden of job creation is falling increasingly to small businesses, which have accounted for the lion’s share of job growth in this economic recovery.

Job growth has picked up in recent months. April payroll gains beat expectations, rising by 244,000 workers, the Labor Department reported on Friday, although the unemployment rate ticked up to 9 percent from 8.8 percent in March. Despite the upturn in jobs, private-sector payrolls are only 787,000 above where they were when the recovery began in June 2009. Employment is still 6.7 million jobs below the pre-recession peak and 2.8 million below the pre-2001 recession.

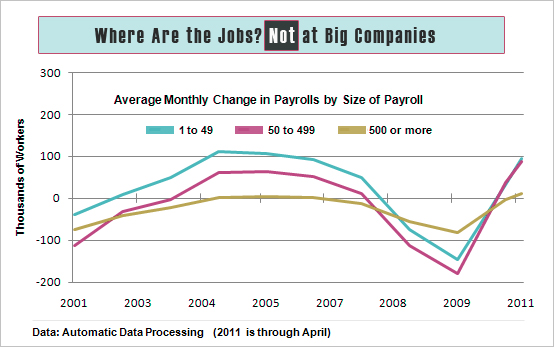

The breakdown of hiring gains by size of private-sector companies is striking. Over the past decade, payrolls of small businesses that employ 1 to 49 workers have increased by 2.6 million, based on data from Automatic Data Processing, while jobs at companies with 50 or more employees have shrunk by 5.4 million. Since the current recovery began, firms with 50 or more workers have generated only 16 percent of private-sector job growth, with smaller businesses accounting for 84 percent of the gains.

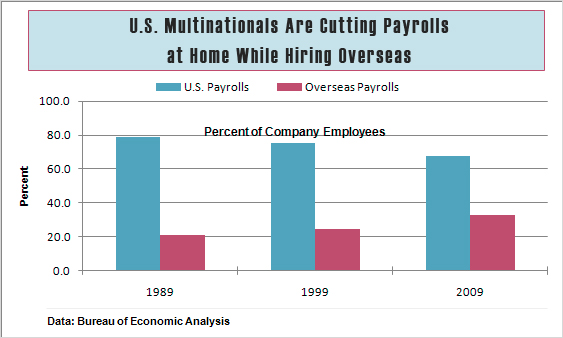

The biggest drag on job creation, both in this recovery and over the past decade, has come from the largest companies, those with 500 or more employees. That’s especially true for big multinational corporations, which employ about one-fifth of all American workers and pay higher average wages than other U.S. companies, according to a study by the McKinsey Global Institute. Payrolls at these large firms have edged up in recent months, but are still below where they were when the recovery began. More important, since 1999, U.S. multinationals have been shrinking their payrolls in the U.S. while beefing up their overseas workforces, according a recent report by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).

Between 1999 and 2009, these large global corporations pared 2.9 million workers from their U.S. payrolls while adding 2.4 million jobs at their foreign affiliates. That’s a reversal from the previous decade, when they boosted payrolls across the board, including increases of 4.4 million in the U.S. and 2.7 million overseas. These companies are simply doing what most small outfits cannot: They are going where the business is. Between 1999 and 2009, BEA says, sales by U.S. multinationals in the U.S. increased by 25 percent, to $7.8 trillion, but receipts from their overseas operations more than doubled, to $4.9 trillion.

Big companies with a global reach also can utilize the sometimes more favorable mix of skills, often at comparably lower wages, in overseas labor markets. Wells Fargo chief economist John Silvia says that for years the U.S. has had an oversupply of low- and semi-skilled workers and a shortage of high-tech scientists and engineers crucial to innovation and growth. In the closed U.S. economy of the 1950s to 1970s, those mismatches were less apparent than they are now in a wide-open global economy. The McKinsey study, while noting the importance of multinationals to the U.S. economy, also raises concerns that a less than optimal U.S. education system and limits on immigration of skilled workers are encouraging companies to invest outside the U.S.

At home, big U.S. corporations, especially manufacturers, face increased pressure from shareholders to maintain healthy earnings amid heightened competition from imports. That means the big guys have more incentive to keep a laser focus on productivity gains and cost control. Small companies with 1 to 49 employees tend to be concentrated in the service sector, where they face far less import competition.

The track record on productivity and costs is clear from last week’s report on first-quarter productivity from the Labor Dept. During the first seven quarters of the recovery, running through the end of March, production in the nonfarm business sector has grown 6.5 percent, while hours worked by employees have increased just 0.7 percent. That means increased productivity, rather than new hires, contributed 88 percent of the growth in overall production, led by a large contribution from manufacturers.

The result has been unusually restrained labor costs this far into a recovery, which has generated exceptionally high profit margins. Earnings for the big, typically global, firms in the Standard and Poor’s 500-stock index continued to top expectations in the first quarter. Among those that have reported results, 69 percent beat analysts’ estimates, well above the typical 62 percent, according to Thomson Reuters.

Even though small companies are hiring, the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB), which represent over 300,000 small businesses in the U.S., says the rate of job creation is historically low, especially for a recovery period. NFIB chief economist Bill Dunkelberg says the reasons are weak current demand and uncertainty about future sales. The latest NFIB survey of nearly 2,000 small companies shows that “poor sales” continues to top the list of business owners’ most important problems, exceeding both taxes and regulatory red tape.

Small companies are heavily dependent on spending within the U.S. at a time when domestic demand, especially by consumers, is fighting strong headwinds, as households shed debt and rebuild their savings. Since the recession ended nearly two years ago, U.S. domestic demand, which includes imports, has not regained its pre-recession peak. Neither have small business payrolls. Meanwhile, big global companies are taking advantage of strong demand in fast-growing economies outside the U.S.

All this suggests that Washington policies that support small businesses, both directly and indirectly by strengthening overall demand, would pay big dividends for U.S. job markets. Likewise, if the U.S. is going to get its share of global growth and new jobs, policies that enhance the attractiveness of America as a place to invest will be imperative, as the structure of the global economy continues to shift.

Related Links:

Waiting on Superman: Good Jobs Report Not Enough to Save the Day (Benzinga.com)

Small Business Hiring Improves in April (thestreet.com)