|

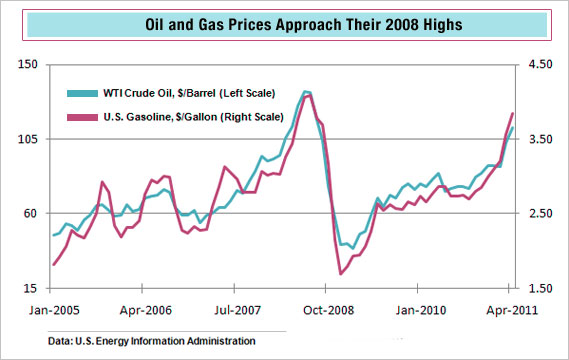

There are plenty of risks in the economic outlook right now, including global supply disruptions following the multiple disasters in Japan, sovereign debt problems in Europe, budget gridlock in the U.S., and China’s inflation and rate hikes. What economists are most worried about, though, is oil. West Texas Intermediate crude ended above $112 per barrel in New York trading Thursday before the Easter break. Brent crude, the European benchmark, was just over $124. The average price for U.S. gasoline, at $3.85 per gallon on Friday, continues its march toward the $4.11 peak hit in 2008.

Already, rapid growth in emerging markets in Asia and South America is pressuring tight global oil supplies. That’s what pushed oil prices to $147 in 2008, adding to the problems in the U.S. economy. The Paris-based International Energy Agency in its April report estimated that effective spare production capacity within OPEC, which supplies about 40 percent of the world’s oil, stands at 3.91 million barrels per day. Based on OPEC’s March production of 29.2 million barrels a day, that means OPEC is producing at just over 88 percent of capacity – leaving a thin margin close to the level that helped drive oil prices up in the previous decade. The turmoil in Libya has already taken most of the country’s 1.7 million barrels per day off the market, and any further supply losses would be acutely felt.

How would oil in the $140-$150 per barrel range play out? Economists say much would depend on the speed of the rise. In the U.S., a spike to that range over the narrow space of a quarter would cause a sharp pullback in consumer spending, mainly on high-priced discretionary items such as cars and home goods. The surge would generate ripple effects throughout the economy, including outsized impacts on transportation, distribution, and construction, while increasing the chance of a new recession. The recent price rise has already pushed up U.S. inflation to an annual rate of 6.1 percent from December to March, cutting spending growth sharply last quarter and hammering consumer confidence.

and gasoline has already wrecked

previously upbeat forecasts for U.S. growth.

In the U.S., the 40 percent spike in both crude oil and gasoline over the past six months has already wrecked previously upbeat forecasts for U.S. growth and inflation for the first half of 2011. Some economists believe first-quarter GDP growth, to be reported on Apr. 28, dipped below an annualized 2 percent rate and some have shaved nearly a full percentage point off their forecasts for the first half, compared to expectations only a few months ago. The worry now is that energy prices may not settle down as forecasters and policymakers have expected, which could add a further downdraft to growth and more updraft to inflation, not just in the U.S. but across the global economy.

For now, most economic forecasts assume that the oil price spike so far is both manageable and transitory, knocking perhaps a few tenths of a percent off what global growth would otherwise have been this year and adding a few tenths to inflation. However, analysts don’t dismiss the possibility that the recent price rise could continue. Political unrest in the Middle East and Africa could intensify and create structural changes in global oil supply, and the nuclear energy disaster in Japan could shift more energy demand toward oil.

Say what you will about the various causes of past U.S. recessions, but economists at HSBC offer a sobering observation. Since the 1970s, a doubling of the real price of oil, which is the oil price relative to overall inflation, within the span of a year has almost always been followed by declining GDP. The two exceptions are the 1990-91 recession, when prices spiked but did not quite double, and 1987, when prices did double, followed by slower growth but no recession. Today, a doubling would require prices to rise to about $150.

Looking across the global economy, separate studies at Morgan Stanley and Barclays Capital do not suggest a total derailment of the global recovery, but do imply a serious bout of 1970s-style stagflation, a combination of sluggish growth with high inflation. The Barclays analysts conclude that a rise to $150, if sustained at that level, would cut global growth by about 0.75 percentage points, while adding as much as 3 points to global inflation. Morgan Stanley, using a different approach, would expect a 1 percentage point loss of growth and 1 additional point in inflation as result of oil at $140. The global economy, including fast-growing emerging markets, is generally expected to grow about 4 percent this year; it is said to be in a recession when growth dips below 3 percent.

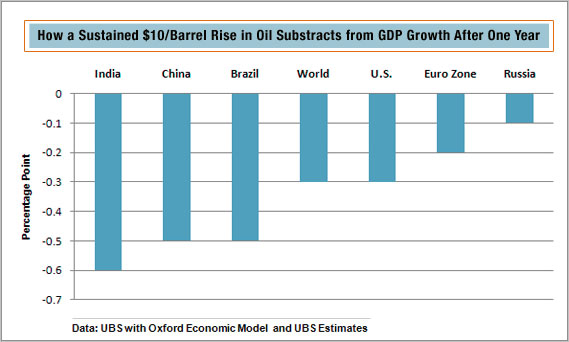

The effects across the global economy would vary, based primarily on how much oil a country imports. Costlier oil boosts inflation leaving less income to spend on other items. “Higher oil prices redistribute income and hence demand from oil-importing economies to oil-exporting economies,” says Morgan Stanley economist Spyros Andreopoulos. Countries with high oil bills relative to GDP, such as China and India, take the biggest hits. Global growth gets squeezed because the shift in income to oil exporters, such as Saudi Arabia and Russia, doesn’t all get recycled back into the global economy. A big chunk is either saved or spent internally.

Morgan’s Andreopoulos dismisses the idea of a magic number for oil prices that would cause the global economy to roll over. A better way to look at the global picture, he says, is that as oil prices rise they transfer more and more income away from oil importers, snuffing out demand, and constricting global growth. The opposite is also true. If prices return to $90, the income transfer would be much less, implying that global growth would be slightly above Morgan’s forecast, which averages 4.4 percent for 2011 and 2012, and that inflation would be slightly below its 3.7 percent projection.

inflexible fiscal policy and still fragile credit markets.

A spike in oil prices would also work against efforts to rebalance global trade. Given the already large trade deficit in the U.S., which is a major source of global trade imbalances, a bigger U.S. oil bill would only widen those imbalances further, say the Barclays analysts. However, the mix would change. Trade surpluses in China and Germany would shrink accompanied by higher inflation, but the surpluses in oil exporting nations, such as Saudi Arabia and Russia, would balloon higher.

The big worry right now is the combination of inflexible fiscal policy and still-fragile credit markets, say the HSBC analysts, especially in developed economies. Their government budgets are already stretched and unable to offer much support in case of a recession, and their economies may not yet be strong enough to withstand the higher interest rates that central banks might use to keep inflation under control. That means a spike in oil prices could not come at a worse time, and once again the global economy is at the mercy of its oil supplies.

Related Links:

U.S. Airlines Results Hit by Soaring Fuel Prices (Reuters)

Oil Prices, Inflation Pose Risk to Global Economy: IMF (Fox Business)

Oil Price Rise Could Trigger Recession, Warn Economists (FT Adviser)