|

It’s been a year since President Obama issued his National Export Initiative, aimed at doubling U.S. exports in five years. So how are we doing? After only one year, we’re already behind schedule, and analysts are starting to wonder if the goal is even achievable. The outlooks for global growth and the dollar, while supportive, may not be helpful enough, and the current policy framework may not be sufficient.

No one doubts the urgency of the president’s initiative, and even partial success would be a plus for the economy. For a country that must begin to live within its means while also creating new jobs, U.S. output will have to speed up relative to U.S. consumption, with more production targeted for overseas markets. Last year, with the global economy growing a strong 5 percent and the dollar low enough for U.S. products to be generally competitive in overseas markets, real exports of goods and services managed to grow just 11.8 percent. Reaching Obama’s goal requires a yearly pace of 15 percent. “Doubling exports in five years may not be impossible,” says Wells Fargo economist Jay Bryson, “but it may be rather difficult to achieve.”

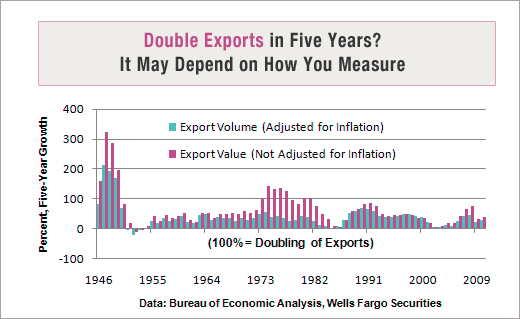

To measure success, Bryson and other economists believe the focus should be on real exports, which are adjusted for price changes to reveal the actual volume of goods traveling abroad, as opposed to export values, where higher prices can inflate actual trade flows. The value of shipments rose 16.5 percent last year, puffed up by a 4.7 percent rise in prices. If the objective is to generate more production and boost payrolls, real exports have a tighter relationship with export-related jobs over the long run.

The U.S. is already under-performing the rest of the world

as an exporter of manufactured goods.

Against that benchmark, history is not encouraging. Real exports have doubled in five years only once in U.S. history, following World War II and the Marshall Plan, when U.S. shipments tripled. Export values accomplished the feat in the 1970s, only with the help of double-digit inflation rates. Plus, given that real exports rose only 11.8 percent in the first year, growth in the final four years would have to average 17 percent per year to reach the five-year target. Wells Fargo’s analysis suggests that even at a continued solid pace of global growth, the dollar would need to fall sharply, a combination they say looks implausible.

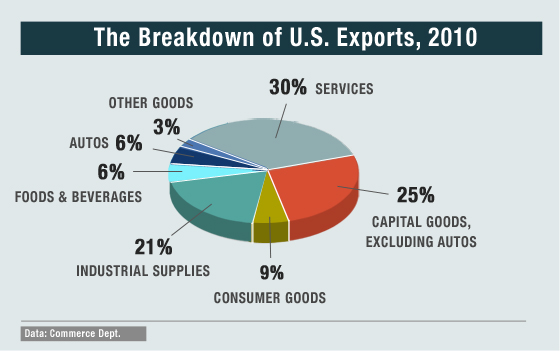

Progress will have to come mostly from exports of goods, which comprise 70 percent of all U.S. overseas shipments while services account for the rest. Real export of goods rose 14.7 percent last year, and perennially slower-growing services increased 5.8 percent. However, the U.S. is already under-performing the rest of the world as an exporter of manufactured goods. It ships abroad only 45 percent as much of its manufacturing output compared to the average of all other countries, according to an analysis by the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM). Although U.S. factories account for about 20 percent of world manufacturing, the most for any country, it ranks 13th globally in the proportion of its manufacturing output that it exports, says NAM. The top three nations are Taiwan, Germany and Korea.

Exports of goods, which tend to move in tandem with the global business cycle, will be especially dependent on economic conditions abroad. That’s particularly true for capital equipment, industrial materials and autos, which make up more than half of all U.S. exports. In that regard, the two-speed global recovery will limit America’s export potential. Recovery in developed economies, which were hardest hit by the financial crisis and account for the majority of goods exports, is expected to be muted. However, the increasing importance of rapidly-growing emerging markets as a destination for U.S. production will take up some of the slack. Developing economies purchase more than 40 percent of U.S. exported goods, with China the third largest buyer.

Boosting U.S. exports means trade policies will be paramount. “Can the U.S. become an exporting juggernaut?” asked Fred Bergsten, director of the Peterson Institute for International Economics at a recent policy conference in Washington. “Yes, but only if the policy framework is right.” Bergsten says what’s needed are more liberal export controls, more free-trade agreements, less restrictive tax policy and a further depreciation of the dollar. (The Peterson Institute is partly funded by Peter G. Peterson, who also funds The Fiscal Times.)

Through 2010, the U.S. has shown a trade surplus with its

free-trade partners for three years in a row, adding up to

$70 billion.

The issues are thorny. Some say U.S. policies are already debasing the dollar at the risk of future inflation. Others, like Bergsten, argue that the greenback is overvalued by about 10 percent, almost totally reflecting overvaluation against the Chinese Yuan. China intervenes in the foreign exchange markets to the tune of about $1 billion per day to prevent its currency from falling against the dollar. Studies have shown that each 1 percent drop in the real trade-weighted value of the dollar lifts U. S. exports by about $20 billion. However, a 10 percent drop from the dollar’s current level would take it to a record low.

Looser export controls involve touchy national security questions, and many politicians think trade agreements only shift U.S. jobs overseas. New agreements have been slow to evolve. U.S. bi-lateral pacts with Korea, Colombia and Panama, have yet to be ratified, and the broader multi-lateral Doha round of trade talks continues to go nowhere. Even so, data show that past U.S. trade agreements have been a clear plus. Through 2010, the U.S. has shown a trade surplus with its free-trade partners for three years in a row, adding up to $70 billion, according to NAM.

Clearly, the odds are stacked against Obama’s goal, if real exports are the target. With a little inflation, doubling the dollar value of exports may be more plausible, but the Export Initiative will be meaningful only if it generates additional economic growth and more jobs. Real exports totaled nearly $1.7 trillion last year, and studies show that every additional $1 billion in exports generates 6,000-7,000 new jobs. At that rate, even if the initiative falls short, economists agree it would be well worth the effort.