When Forbes began tracking the wealth of the richest 400 Americans in 1982, it only took $75 million to make the low end of the list. Today, $1 billion is the minimum requirement. If you added up the net worth of the 51 richest Americans last year, the trillionaire mark would be reached. This year, that number is down to 37 individuals. Twenty years from today, will it take only one?

When will the 21st century's first trillionaire be created?

It is a matter of when, not if, according to many wealth experts. Steve Kraus, the chief insights officer of Ipsos MediaCT, which releases an annual survey on wealth, said he would not be surprised to see a trillionaire within the next 25 years.

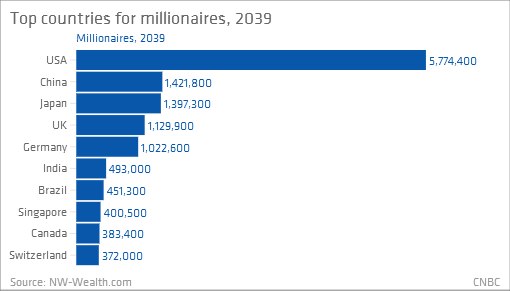

Andrew Amoils, senior analyst at South Africa-based global affluence tracker New World Wealth dared to be even more specific. Taking into account variables including GDP per capita, wealth per capita, commodity price, exchange rate and price-earnings ratio forecasts—as well as the outlook in specific countries including the U.S., Russia and India—he said there is an 11 percent chance of a trillionaire within the next 25 years (with the U.S. being the most likely domicile, followed by India, which will see the greatest number of new millionaires created by 2039).

Related: Get Used to It: The Rich Do Get Richer

"This is a geometric trend. It's not an incremental progression," said Paul O'Brien, an Oxfam vice president who is studying the impact of wealth on global policy. "Existing wealth has a greater capacity to accumulate wealth. ... If we are now at 37 individuals to reach a trillion, will we be down to five people in 2039, with $200 billion each, and 65 years from now, turn those five into one?"

The Forbes 400 aggregate wealth has increased from under 1 percent of national wealth to 3 percent since 1982—even as its ranks have decreased as a percentage of total population. According to tax lawyer Bob Lord—who has become something of an elite wealth wonk since his professional work planning estates in recent decades led him to become acutely aware of the issue, "We're sliding back to Gilded Age levels of wealth concentration. My guess is 2039 is the most likely time frame to cross that threshold."

Who will the first 21st century trillionaire be?

Today, Bill Gates has 3.6 percent of the Forbes' list's wealth. Aggregate national wealth has increased from about 10 trillion to 70 trillion since 1982. So, let's do some wealth wonk rough math, and even be a little conservative in the process.

Say the next 25 years are not quite as robust in terms of aggregate wealth creation, and we're only at $300 trillion in 2039 (rather than the $490 trillion that would result from taking the recent national wealth acceleration and extrapolating). And let's say the Forbes 400 share reaches 8 percent of that national wealth—it has been tripling over the previous three decades. That would put the Forbes 400 at $24 trillion total, and, "Even if the guy at the top has only the share that Gates has now, he/she is awfully close to the magic number," Lord said. That would be $846 billion, to be exact.

That scenario may not be the most likely. In fact, several wealth experts expect it will take several Bill Gates-like successes from one individual to reach the trillion-dollar mark. "It might take the founder of five of today's Microsofts to reach a trillion, but we're going to see larger and larger Microsofts," Amoils said. "Think of what folks would have said in 1980 about the prospect of having a $100 billionaire in 25 years, yet Gates reached that level in the 90's," before he started giving away large blocks of Microsoft shares to his foundation and as Microsoft matured, its stock value declined.

Related: 9 Youngest Billionaires in the World

The super-serial entrepreneur seems to be the odds-on bet.

"It will take a series of grand slams," said George Walper, president of Spectrem Group.

"You will have to really hit it big and double down on the next big thing," Kraus said.

Elon Musk may be the closest thing to this mythical individual now being imagined creating a series of huge enterprises and turning them into the largest personal fortune. The market, at least, does seem poised to accommodate such a series of events.

The growth of technology and ability to take companies public is happening much faster than it did historically, and the diffusion time for innovation to work itself through our lives is getting shorter.

"There is so much money floating around and the multinational companies that exist today ... the only really large companies before were car companies. Now we've got all these huge tech companies globally based," Amoils said.

What will drive wealth creation—and accumulation?

This trillionaire question is another way of asking what wealth trends will dominate in the 21st century, and either help or hurt the would-be trillionaire on their ascent. Here are a few the experts highlighted.

1. Luck

Warren Buffett quips that he won the ovarian lottery—the right country, the right generation—and for every Mark Cuban who got rich from a technology bet right before a big crash but was smart enough to diversify and use hedges to protect his wealth, there are plenty of examples of the big winners who lost it all—too much and too fast to ever make up the difference again, or simply couldn't come up with a second big idea to grow their wealth exponentially.

The idea of a serial entrepreneur hitting the "grand slam" runs into some trouble when luck is added to the equation.

Kraus provided one example. A person he knew well started an Internet networking company in the early '90s and it took off—it was hard to not take off making routers in the early '90s. After a stint in early retirement, the tech executive decided to do it all over again and make a better, faster Internet box—it came out right in time for the dot-com crash when you couldn't sell another box. The company went under and sold for nothing. The executive is now in private equity. "The second time around teaches entrepreneurs about luck and market timing," Kraus said.

"Striking gold once is hard, twice is really difficult and to get there three or four times, even harder," Walper said.

Related: Guess How Much Money Warren Buffett Made in 2013?

2. Hidden wealth

In his recent tome "Capital in the Twenty-First Century," Paris School of Economics professor Thomas Piketty notes that the amount of money circulating around the globe as an input and output simply doesn't add up—unless people are investing in real estate on other planets. Hidden wealth may be one of the biggest drivers of accumulation of capital into fewer hands.

A guy like tax attorney Bob Lord can become an expert in billionaires because the fact of the matter is few institutions are able to systematically track the data. Piketty's pickings were slim when he tried to find the data, and he points out that while Forbes data are likely flawed, they may still be the best out there. He chides governments around the world for doing such a poor job of tracking wealth.

What governments have been very good at is providing an increasing number of tax havens. "When you start getting outside Western civilization, how much wealth is even known as opposed to hidden?" Walper said.

In the U.S., it is harder to hide huge sums of money because starting a company and taking it public is the typical route, and that's when the scrutiny begins. "The really wealthy overseas have much greater motivation and ability to hide wealth," Kraus said.

There are rumors about families like the Rothschilds sitting on sums of money no one can know even to this day and, within the United Arab Emirates, a handful of sheiks who are worth billions but are off the personal wealth radar because their fortunes are technically government assets. "I think if you include the sheiks, they might pass Carlos Slim or Gates or Buffett," Amoils said.

3. Philanthropy

Big-hearted billionaires could be one of the biggest limiting factors to the creation of a trillionaire. Buffett and Gates have been the most vocal with their Giving Pledge campaign to convince the world's richest to leave a majority of their fortune to philanthropic preferences.

"This Buffett/Gates approach has broad appeal," Kraus said. "Really wealthy people now are taking greater steps to distribute wealth in their own lifetime. ... To extent the extent that there is a limiting factor on someone becoming a trillionaire, this might be it," Kraus said.

Another way to think about Bill Gates' focus on nonprofit work is, simply put, boredom. "If you take an ambitious, talented person with a zero net worth, accumulating wealth would be reasonably high on their list of priorities," Lord said. "But as net worth goes up, most folks lose interest. I doubt Bill Gates thinks much about accumulating more wealth these days, and he certainly doesn't dedicate his time and energy in that direction. ... The same could happen to Elon Musk."

But philanthropy may not serve as a limiting factor for all, and in the end, this may just ensure that the greedier billionaires will take the lead from Buffett and Gates. "Some people, like Sam Walton and the Koch brothers, they never seem to lose focus," Lord said. So the boredom factor ultimately will not preclude a trillionaire—and not necessarily lead to a Giving Pledge commitment.

4. Taxes

If the U.S. is going to be able to boast the 21st century's first trillionaire, tax policy will have to continue on its current path.

When Ronald Reagan took office as president of the United States, the top personal income tax rate in the U.S. was 91 percent. Tax policy in the U.S. in recent decades has figured prominently in wealth accumulation.

Related: Venture Capital Investment Climbs to Dotcom-Era Levels

Kraus sees few signs of this trend reversing. "From a social standpoint, the rich are getting richer, yet the notion of social mobility is so central to the fabric of America, and people buy into that even if it's against their own best interest." Income inequality and redistribution of wealth have not been in the top set of considerations for voters. "I don't see a pressing desire by the electorate or D.C. to change," Kraus added.

Oxfam conducted an assessment of how much presidents talk about income inequality—or proxies for that term—in State of the Union addresses over a hundred years, and found a massive amount of variation, O'Brien said. "There were eras where if you didn't talk about it you had no chance of succeeding. In 1912, we had four progressives and a socialist running for president."

Since LBJ's war on poverty there has been a significant falling off in that conversation, and that trend exacerbated under Reagan.

"The money will have to come from somewhere to deal with debt and the deficit, so the 'tax the rich' philosophy will make some gains" but it won't reverse the trend and will only limit even greater concentration, Kraus said.

Forget the single trillionaire—who (and what) will really own the 21st century?

For economic researchers including Piketty, the single individual at the top of the list and the total dollar figure they reach is less important than the trends that accelerate income inequality. But you can't stop at the trends, either. The real question is: Who and what will own the 21st century, literally.

Here is a sampling of the "trillionaire" players that may loom large in the 21st century.

The individual-institutional trillionaire complex

Trillionaire investors need to become more inventive with investments across currency, natural resources, agriculture and real estate, among other assets, because there's little left to buy for them. Piketty noted that oil states could decide to buy the entire real estate portfolio of the globe and live off the rent. The point is, "Individuals and investment entities will compete," O'Brien said. Being a trillionaire means having enough money to buy a country or change the price of a commodity like grain or corn—or lift every single person, not just out of extreme poverty, but practically into the middle class, O'Brien said.

The new oil barons

In East Africa, 130 trillion cubic feet of gas, and more than 2 billion barrels of oil have been discovered in the last three years. Mozambique, which languishes near the bottom of the global development list, just found enough oil and gas to drive $10 billion a year of revenue for each of the next 40 years—that's $400 billion for the second-poorest country in the world. But into whose hands?

"It's an opportunity and a threat," O'Brien said.

Ex-national oligarchs

Piketty envisions in the future oligarchs for whom nationality is a vestige of a former era.

"National borders could be less important than oligarch borders," Amoils said. "A lot of people already see the ultra high-net worth as fully mobile and they really don't have a permanent place to stay."

Related: How Income Inequality Can Hurt the Economy

All in the family

From 1990 to 2010, Bill Gates grew his wealth from $10 billion to $50 billion. A L'Oreal heiress, meanwhile, grew her wealth from $5 billion to $25 billion—the same rate of growth for doing nothing more creative than investing her family fortune like an elite entrepreneur or institution.

The declining estate tax and shrinking family sizes increase the likelihood of a second-generation trillionaire. "There's a case to be made that some folks will be able to break through the limits on wealth accumulation without creating new Microsofts," Lord said.

This article originally appeared in CBNC.

Read more at CNBC: