Senate Finance Committee Chairman Max Baucus said Tuesday he has instructed his staff to explore ways that Congress might assist the city of Detroit in getting through the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history.

“I think it’s worth exploring, because it’s a big problem,” Baucus told The Fiscal Times in an interview. “I’ve asked my office to look at it, but they haven’t gotten back to me yet. But somebody’s going to look at it.”

Until now, lawmakers, the Obama Administration, Republican Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder and even the city’s emergency financial officer, Kevyn Orr, have discouraged talk of a federal bailout of the Motor City, which formally filed for Chapter 9 federal bankruptcy protection last Thursday.

Vice President Joe Biden acknowledged last week that “we don’t know at this point” what types of aid can come from Washington. A few house Republicans were reluctant earlier this year to support a $60 billion Superstorm Sandy bill that was laden with pork, so it’s unlikely they would endorse aiding a city government infamous for its corruption and mismanagement.

House Appropriations Committee Chairman Hal Rogers (R-KY) joked with a reporter yesterday that with a federal debt of over $16 trillion, “We’re in worse shape than Detroit …. Maybe we should go to them for help.”

While Baucus was vague as to what -- if any assistance – Congress could provide, he mentioned Detroit’s two troubled pension funds that he said deserve federal attention. Those funds – one for general employees and the other for police officers and firefighters -- together account for $3.5 billion of the city’s $18 billion overall debt.

There are 8,200 retired police officers and firefighters but only about 3,000 others working and contributing to the system, which has made it very difficult to maintain. Retirees and their union officials fear that retirement benefits might be reduced or slashed as part of any debt restructuring agreement that eventually emerges from the bankruptcy proceedings.

Baucus, who announced recently he would retire from the Senate next year, has teamed up with House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Dave Camp (R-MI) to try to drum up interest in major individual and corporate tax reform this year. They are scheduled to speak jointly at two small businesses in Philadelphia next week.

The Senate Finance Committee’s jurisdiction ranges from the federal tax code and revenue to government insured pensions and Medicare and health care issues. The committee was a central player in shaping President Obama’s Affordable Care Act .

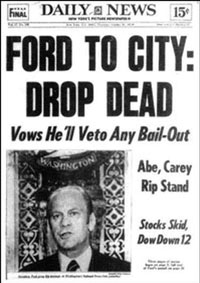

Whether there is a role for the federal government in dealing with the historic bankruptcy crisis is hard to predict at this point. In 1975, when New York City was close to bankruptcy and approached the federal government for help, they were rebuffed. The iconic Daily News front page, headline, “Ford to City: Drop Dead” summed up the response. As a result, city officials and union members negotiated a deal and saved the city from bankruptcy.

SLIDING INTO BANKRUPTCY HELL

Detroit’s 60-year slide into bankruptcy was caused by trends that will be difficult to reverse: A shriveling population – down from 1.85 million in 1950 to 700,000 today, the demise of the auto industry before it underwent a revival, , riots, unimaginable urban blight, poor schools and a fast dwindling tax base.

Orr said last weekend on “Fox News Sunday” that “We are not expecting the cavalry to come charging in” to help the city, and that “we have to fix it because we dug the hole.”

But some lawmakers and budget and policy experts think the federal government could soften the blow on many of Detroit’s beleaguered residents and retirees short of a massive federal bailout like the one that helped save the auto industry.

Currently, the city receives just 6 percent of its $2.6 billion in annual revenue comes from the federal government, according to Detroit’s 2013 budget. Most of that money is received in the form of community development and community services block grants, transportation funds and other assistance.

But maybe more can be shaken loose. Sen. Carl Levin, D-Mich., a one-time chairman of the Detroit City Council, said yesterday that he and others in Washington should be looking closely “at every single federal program, where there are funds available for various things -- from removing blighted houses to transportation to brownfields to education grants, to everything else the federal government is involved in.”

“We should be looking at existing programs to see where there are funds in those programs and then for the city to make out a case that, within existing programs, there are things that can be done without some new bailout.”

Levin said that new legislation would not be necessary. Instead, it would be up to the Obama administration to decide whether to shake loose additional money for the reeling Motor City.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development alone has 122 separate programs for rehabilitating neighborhoods, building housing, removing abandoned buildings and forging public-private partnerships.

Republican Sen. Rob Portman of Ohio said that the administration could also assist Detroit by reviewing federal regulations and mandates that are adding to the city’s cost of operating.

“In my own home state of Ohio, we get lots of input from our bigger cities about Environmental Protection Agency mandates on storm water for instance, and combined sewer overflow,” Portman said.

“I think this is an opening for us to look at some of those policies and mandates,” he said.

Andrew Reamer, a research professor at the George Washington University Institute of Public Policy, said the White House could, if it wanted, convene an ad hoc taskforce of agency officials running all of the programs and decide to organize a coordinated response.

However, the administration must be cautious in taking action in the early stages of the highly complex and high-stakes bankruptcy proceedings, said Reamer, an expert on statistics and regional economics and innovation.

“If I were in that situation, working for the feds or working for the White House, I would be loath to do anything publicly until I understood what the relationship of the federal government should be to the bankruptcy itself,” he said. “Because you don’t want the feds going in there and screwing up the legal process.”

Tracy Gordon, a Brookings Institution fellow in state and local public finance, also cautioned that even if the administration offered Detroit flexibilty on federal programs and mandates, technical assistance or even additional funds, “I just wonder how much that helps in the grand scheme of things.”

“If the federal government were to really step in and loan them money, that would be something else,” she said. “But giving them more flexibility around the edges with grants, I don’t think will make a big difference.”