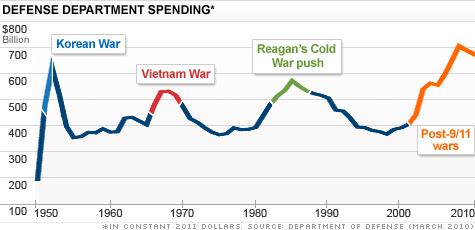

Nearly everyone outside of the Pentagon agrees that a $600 billion cut over the next 10 years, part of the sequester requiring DOD to cut $41 billion from its budget this year, is sorely needed. Over the last decade, war spending has been out of control: In 2001, the Pentagon’s budget was $291 billion. It peaked at $708 billion in 2011, and was $524 billion last year.

These huge budget numbers reflect 20th century war strategy, in which enemies are defeated with tanks and massive armies. DOD’s budget over the last decade did not evolve with changings threat. It was not structured to fight a modern war that will be won by computer hackers, drones and special forces.

In a speech at the Naval War College last month, Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel acknowledged this fact. He told military brass and civilians working for DOD that threats to national security “do not necessarily lend themselves to being resolved by conventional military strength….America does not have the luxury of retrenchment-- we have too many global interests at stake, including our security, prosperity and future. If we refuse to lead ... someone will fill the vacuum.”

High-ranking Pentagon officers have been warning for months that these kinds of changes to the Pentagon’s budget would put the country at risk. They would gut military capacity and decimate morale.

But according to a Fiscal Times analysis and to defense strategy experts, fundamental changes to the way the Pentagon defends the country -- and the way it spends money -- are years down the line. DOD is still trying to wage 21st century warfare with a 20th century budget.

The 2014 Defense budget request does not substantially reduce spending in any of the areas identified by DOD as bloated or in need of drawdown. It’s larger than the 2013 budget by $2.6 billion and pretends as if sequestration is simply going to disappear.

Big projects, like the F-35 fighter program, continue to be funded. The budget did not contain troop reductions from 2013 levels. Missile defense spending decreased by just $550 million from $9.76 billion in 2013.

Mackenzie Eaglen, a security studies fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, says DOD complaints of immediate pain caused by declining budgets are overstated.

“We’re seeing where defense official rhetoric is growing,” she said, referring to statements by Pentagon brass. “But budget submissions are lagging indicators that follow these larger transformation efforts which usually take years.”

In fact, so-called pivots to new global hot spots will occur over decades. These pivots also turn DOD attention away from areas like South America and Africa, where experts warn that new and dangerous threats to American interests are lurking.

PIVOT TOWARD DOD’S BACK-OFFICE

Much has been made of the Pentagon’s so-called pivot toward Asia. The shift does not signal the U.S. intention to fight a war against China or North Korea, and will take place over decades. But the Pentagon does want to increase its presence in this part of the world to counterbalance China’s growing power and North Korea’s unpredictability.

“The pivot, that’s a long-term goal. That is something that the Pentagon will thrive to achieve in the next 10 to 20 years,” she said. “For now, the Middle East, Iran in particular, is the main focus.”

The changes that are involved in this pivot – a reduction in ground forces, a renewed focus on air and naval power, and a growing arsenal to turn back and conduct cyber warfare – will take place over that same period of time. This is reflected in the president’s budget request, which does not significantly reduce force size in the coming year.

Jacob Stokes, a fellow at the Center for New American Security, said the goal of the future force creation would be to train soldiers to perform multiple duties, eliminating redundancies within the services.

“In the future, DOD will focus on the concept of reversibility, meaning bringing down the size of ground forces, but having the people and platforms that would allow you to scale them back up quickly,” he said.

The most immediate change to DOD spending is not materially impacting the military, but the Pentagon’s enormous bureaucracy. Hagel mentioned this is in his War College speech, saying, “Despite good efforts and intentions, it is still not clear that every option has been exercised or considered to pare back the world's largest back-office.”

Eaglen notes that even these shifts are not occurring immediately. The only concrete cost saving measure is a promise to evaluate whether bases could be closed, but this does not guarantee that these closures would actually occur.

“There is very little of that in the 2014 request,” said Eaglen, referring to staffing reductions and cuts to spending programs. “It’s light on compensation shifts and contains little acquisition reform.”

NEW THREATS EMERGING

In the past, the Pentagon has had trouble focusing on multiple threats. For instance, the mission in Afghanistan all but was forgotten once the Iraq War began, just as Iraq was ignored when attention was turned back to Afghanistan.

The Pentagon has already signaled its intention to dismantle much of its European operation. It’s made clear that it would only engage in in so-called “small wars” in Africa, sending drones or Special Forces in support capacity. And Southern Command chief General John Kelly recently told Congress that sequestration has reduced his forces’ capacity to track and capture illegal drug shipments.

“It’s a zero sum game,” Eaglen said. “Counterdrug operations are being shortchanged right now to meet demands in the Middle East and the Pacific.

According to Eaglen, this kind of budgeting could put the country at risk by ignoring ties between organized crime and terrorism. The Drug Enforcement Administration has already identified links between al Qaeda and drug trafficking.

“At the end of the day, the threats are transnational and can’t be confined to one region,” she said. “You can’t take the eye off the ball in South America if you want to stop terrorism in North Africa.”