Money may make the world go round, but some places spin faster than others. Tokyo, for example, has regained its title as the world’s most expensive city in an annual cost-of-living survey released last week by the Economist Intelligence Unit. It’s a familiar, if dubious, distinction for the Japanese capital, which also tops similar recent lists from consulting groups Mercer and ECA International and has been first in the EIU’s rankings for most of the past 20 years.

Among U.S. cities, New York and Los Angeles are the most expensive, though Vancouver is still the most expensive location in North America, 6 percent more expensive than the Big Apple.

New York is closing the gap, though, because of a strong dollar and rising costs, particularly for clothing, tobacco and groceries. In fact, 112 of 131 global cities saw their cost of living fall relative to New York, with costs relative to the Big Apple rising in just 12 of the cities surveyed. Overall, New York rose from 27th to 19th place in the rankings. If you can make it there, you can make it almost anywhere.

RELATED: The Real Cost of Living: $150,000 Minimum

What do those rankings really mean, though? As Carl Bialik points out in a pair of pieces at The Wall Street Journal, the methodology behind such rankings gives them limited usefulness. “Though these rankings usually are reported as if they are universal, they are based on the spending habits of a tiny sliver of the population: expatriates at an executive level who take their spending habits with them around the globe,” Bialik writes.

So while the rankings may help figure out how much globe-trotting executives should be paid when they hop from one continent or city to another, they are far less instructive for locals. “The fundamental flaw of all cost-of-living surveys is that they convert local prices into U.S. dollars, which means that any changes are as much the result of currency fluctuations as of price inflation,” the City Mayors Foundation notes in a rundown of various such surveys.

Caracas, for example, ranks ninth in the EIU survey, but that ranking is skewed by a fixed official exchange rate between the Venezuelan bolívar to the U.S. dollar. “In fact, using a parallel ‘unofficial’ exchange rate for the bolívar of around 14:1 for the last year would make Caracas the joint cheapest city in the ranking, alongside Mumbai and Karachi,” the EIU rankings explain.

For Zurich, currency effects drove expenses down 39 percent relative to New York, dropping the Swiss city from the world’s most expensive a year ago to seventh place this year – even though prices for locals haven’t changed much. The euro has also gained strength since data for the EIU’s report was collected, Bialik notes, so American cities would fare better using current data.

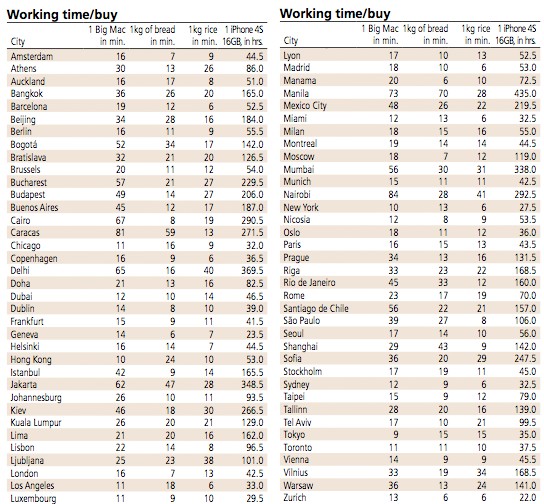

The rankings look quite different when local income levels and prices are compared – in other words, when rankings account for the purchasing power that local wages provide. Mumbai may be the least expensive city in the EIU rankings, but it takes an average of 56 minutes of work to earn enough money to buy a Big Mac there, according to a UBS report (PDF) released in September 2012. Buying an iPhone 4S (the report came out before the iPhone 5 did) would take 338 hours of work in Mumbai, based on the weighted net hourly wage in 15 professions. In New York, by contrast, it takes 10 minutes to earn enough for a Big Mac and 27.5 hours for an iPhone.

RELATED: 7 U.S. Cities with the Biggest Bang for Your Buck

Workers in Zurich are able to afford the iPhone the quickest (22 hours of work) while those in Manila would have to put in 435 hours, the UBS report found. Workers in North America and Western Europe have to put in less than 50 hours on the job to buy the smartphone, UBS reported, while those in Eastern Europe, South America, Asia and Africa would require, on average, “considerably more than three weeks’ salary.”