As the fiscal cliff negotiations continue in Washington and the stock market seemingly turns on every expression of optimism or disappointment, what’s really at stake, in the near term at least, is the answer to two important and interrelated questions: How dysfunctional is our political leadership and how bad is our economy going to be next year?

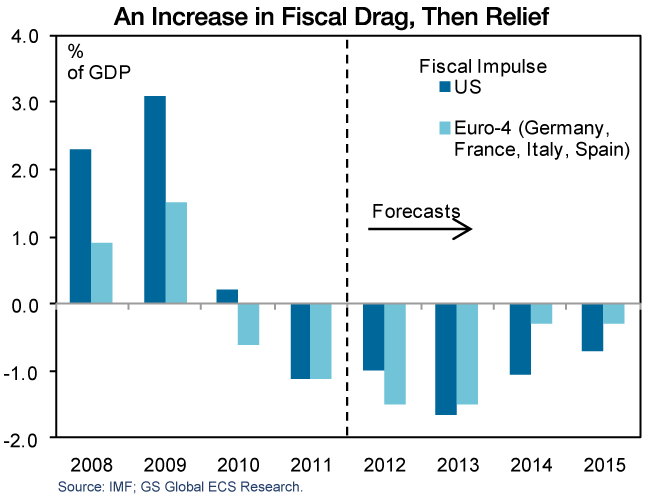

The two questions are connected because fiscal policy, both in the U.S. and in Europe, has already been a drag on economic growth, and it’s extremely likely to continue to be one as politicians look to begin addressing concerns about long-term debt burdens. The debate about the fiscal cliff deal might revolve around the preferred paths to reducing the nation's long-term debt, but it also will determine just how much fiscal policy will limit growth over the coming months and years.

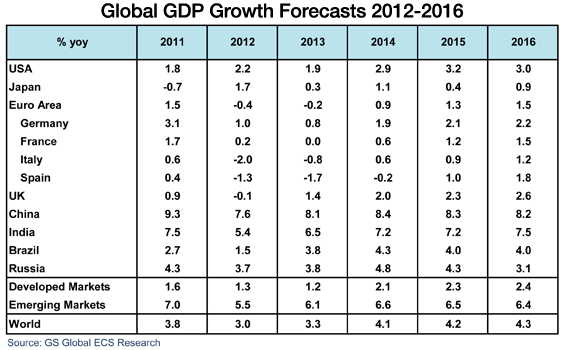

No matter what, we're unlikely to see gangbuster growth next year. The forecasts from economists — even those who are optimistic about things moving in the right direction — certainly aren't all that encouraging. Nominal growth through the first nine months of 2012 has averaged 2 percent, and a survey of 39 economists by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia released earlier this month found that, on average, they predict real GDP will grow 2 percent in 2013, before picking up to 2.7 percent in 2014 and 2.9 percent in 2015.

Those levels are still below the 3 percent or more needed for the economy to be considered healthy, and fiscal tightening is a key culprit in the projected sluggishness, particularly in the first half of next year. The fiscal drag should peak next year, increasing from 1 percent of GDP in 2011 and 2012 to 1.75 percent, Goldman Sachs economists say. Their projections assume that both the payroll tax cut and the Bush income tax rates for high earners expire at the end of the year, and also factor in new health care taxes, the winding down of emergency unemployment benefits, discretionary spending cuts from the 2011 budget agreement and the end of the 2009 stimulus package.

Of course, the projected growth rate, low as it already is, and the amount of government drag on the economy both depend on whether a deal is reached to avoid the fiscal cliff, and the ultimate shape of any compromise. “If resolution of the ‘fiscal cliff’ remains elusive and/or the size of the fiscal tightening ultimately agreed is even larger than we have assumed, a new recession could result,” Goldman’s economists wrote in a note released Wednesday.

“Don’t misunderstand this story as an argument that government budget consolidation is not needed,” Goldman’s chief economist, Jan Hatzius, said Wednesday. “It is needed over the medium-term, as most of the major advanced economies have long-term budget imbalances that will ultimately require significant consolidation.

“The point we’re making is a little different. The point is that this consolidation is imposing some very real near-term costs on economic growth, which are all the more painful in an environment where the economy is still far below full employment. So it’s very important, in our view, to be careful not to overdo the speed of the adjustment, and especially in early 2103 there are some real risks that policymakers will overdo it.”

The good news is that once we get over that 2013 hump, assuming that the private sector continues to heal and doesn’t freeze up in the face of daily images of contentious Washington deal-making, global growth could improve at least a bit, Hatzius, and his team wrote in a note issued Wednesday: “Assuming the world can ‘muddle through’ the weakness we expect early in the year as a consequence of even greater fiscal contraction, growth should pick up in the second half of the year.”