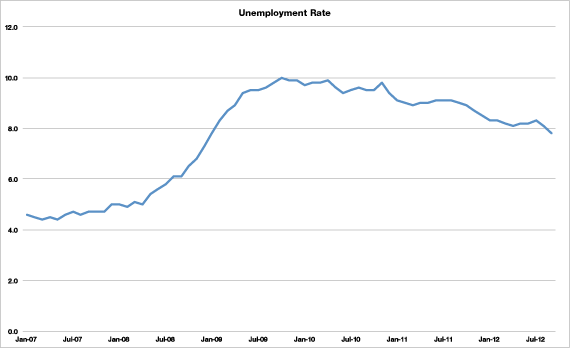

While much of the coverage of today’s September jobs report has centered on its impact on the presidential election, the data behind the surprising drop in the unemployment rate to 7.8 percent also tell an interesting story about the changing nature of the U.S. workforce.

The economy may be moving into a new era, one where reports on the labor market may be skewed by the growing proportion of Americans near or entering retirement. For workers in their prime earnings years – those aged 25 to 54 – the unemployment rate fell in September to 6.8 from 7.1 percent in August. It was 8.1 percent a year ago.

The presidential contenders gave their obvious and uninformative spins to a September jobs report: that showed the unemployment rate dropping to 7.8 percent, the lowest level since the day President Obama took office.

The presidentPresident Obama said things are moving in the right direction. -the 7.8 percent unemployment rate is the lowest level since the day he took office. He Obama hailed the creation of 114,000 new jobs and the welcome uptick in the labor force participation rate. Yet he admitted that more needs to be done to “help our friends and family who are still looking for work.”

Republican challenger Mitt Romney asked “why are there still 23 million Americans looking for work?” He claimed only a change in White House leadership could return the economy to the more robust economic growth needed to rapidly bring down the unemployment rate.

But those sound bites ignored some positive trends in the jobs data that suggest the economy may be moving into a new era, one where reports on the labor market may be skewed by the growing proportion of Americans near or entering retirement. For workers in their prime earnings years – those aged 25 to 54 – the unemployment rate fell in September to 6.8 from 7.1 percent in August. It was 8.1 percent a year ago.

The current level for these prime age workers is about where the unemployment rate stood in the mid- to late-1980s, which was the last time one large generation – dubbed by NBC news anchor Tom Brokaw as the Greatest Generation – moved toward retirement while another very large cohort – their children, the 77 million baby boomers – were just entering their prime earning years. Unemployment during the Reagan administration didn’t drop below 6 percent until his last year in office.

Meanwhile, there was also positive news in Friday’s jobs report for newest entrants into the labor force, those aged 20 to 24. Their unemployment rate went from 15.2 to 13.7 percent. While that’s still unacceptably high, it was a sharp improvement.

So what’s happening to older workers? There we see some intriguing data in the household survey, which is usually considered less reliable as an indicator of new jobs. The telephone survey of 60,000 households generates both the unemployment rate and demographic data for the Labor Department.

Take, for instance, its finding that a stunning 873,000 more people claimed to be working last month. About two-thirds of those jobs were part-time. Moreover, self-employed workers jumped 144,000 in September and are now 429,000 higher than a year ago. Given that both the payroll and household surveys show the economy added 1.3 million jobs since the beginning of the year, it would appear a substantial share of total new employment is among the self-employed.

Who are these people? According to labor economists, many employers have outsourced key support functions like accounting and other business services. Many information companies operate with virtual staffs who work on a contingent, part-time or contract basis. Older workers, including millions who lost their jobs during the Great Recession, have become freelancers or consultants and wind up filling these slots. They may not show up in the payroll report.

Many others at or nearing retirement opt for “part-time” work, even though when they are working it is full-time, often earning as much or nearly as much as they did when gainfully employed. When called by a surveyor, they may answer “no” when asked if they have a job even if they’re working full-time on a short-term contract.

“How people answer this question is a little bit how they feel in their gut,” said Linda Barrington, managing director of Cornell University’s Institute for Compensation Studies. “They may not be unemployed, but they’re always looking for work. This is becoming a bigger and bigger part of the economy.”

And then there’s the simple demographic reality that 10,000 Americans are turning 65 every day as the baby boom crosses the line that used to be considered the threshold of retirement. They account for a significant proportion of the decline in the labor force participation rate.

“Some of the decline in labor force participation – I would estimate about a third – since the beginning of the Great Recession would have happened anyway,” said Heidi Shierholz, a labor economist at the Economic Policy Institute. “It’s structural.”

Still, that doesn’t explain away the sluggish performance of the economy and the inadequate level of payroll job creation, which is where most Americans, especially those without a college or two-year degree, look for jobs when they’re unemployed. Their job market reflects the sluggish housing recovery, slowing manufacturing growth and export headwinds from Europe and China.

Economic growth below 2 percent is far too low to rapidly reduce the unemployment rate. “At the current rate, it will take more than a decade to reach full employment,” wrote Dean Baker, an economist at the Center for Economic Policy and Research.

The payroll numbers have yet to suggest the headwinds buffeting the economy are reversing themselves. While the private sector added 104,000 jobs overall, manufacturing lost 16,000 jobs. Construction gained a paltry 5,000 new slots, far too few slots to provide hope for the millions of blue-collar tradesmen out of work.

The big gainers came from the usual suspects. Health care led the parade by adding 29,800 jobs or more than one in every four new slots. While that could slow if the limits on Medicare in the Affordable Care Act go into effect, Romney has promised to restore those cuts. That would be a renewed boon to health care job growth. But it would have to be paid for either through increased deficit spending or higher taxes, which would sap job growth in other sectors of the economy.