Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney finally dangled some possible specifics about how he could slash all marginal tax rates by 20 percent and not blow-up the deficit—cap deductions at $17,000.

Tax policy experts will suss out competing models of how this idea to broaden the base would impact government revenues and deficits that have pushed the outstanding national debt to the size of the $16 trillion U.S. gross domestic product.

While Romney only speculatively floated the idea in an interview with a Denver television station Monday night, it helps insulate him from criticism ahead of tonight’s presidential debate about the vagueness of his plan. But a proposal that potentially raises taxes on wealthier Americans—a definite possibility if deductions are capped—might also undermine Romney's own argument for how his plan would drive economic growth better than Obama's.

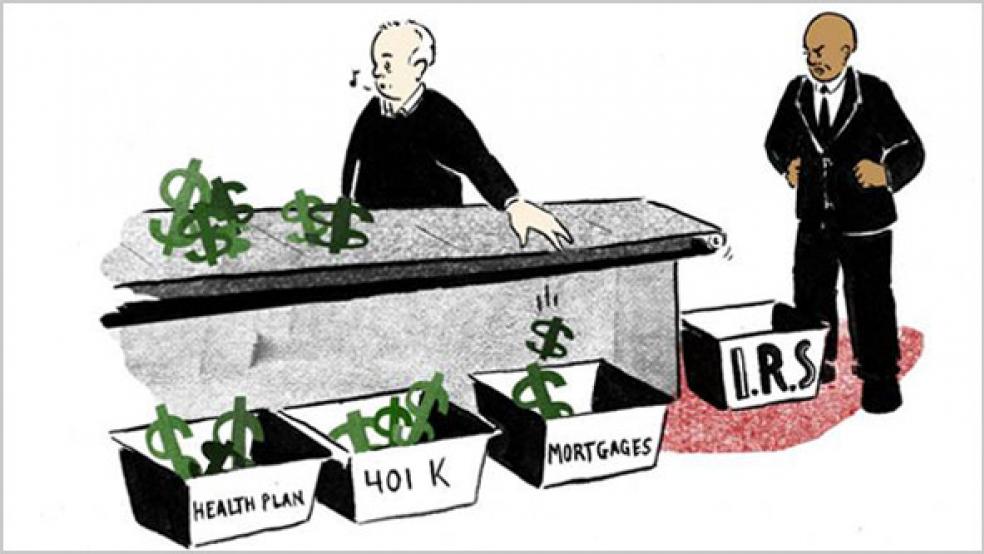

“As an option you could say everybody’s going to get up to a $17,000 deduction; and you could use your charitable deduction, your home mortgage deduction, or others — your healthcare deduction, and you can fill that bucket, if you will, that $17,000 bucket that way,” Romney told Denver’s KDVR. “Or you could do it by the same method that Bowles-Simpson did it where you could limit certain deductions, but that’s the sort of thing you do with Congress.”

Romney campaign spokeswoman Andrea Saul maintains the goal involves cutting taxes for the middle class. "There are a range of policy options, Gov. Romney referenced one illustrative example, to achieve these goals," Saul said in an emailed statement to CBS News.

Obama has also proposed limiting deductions for wealthier taxpayers for the past four years—so Romney is really only differentiating himself in policy details rather than principles. The president would limit the tax benefit of itemized deductions to the 28 percent marginal tax rate.

“It’s a great idea because it would reduce a large tax subsidy (i.e., ‘tax expenditure’) for those who need it least, improve the economic efficiency of the tax code and raise revenues that could be used as part of a deficit-reduction package,” Diane Lim Rogers, the chief economist of the nonpartisan group Concord Coalition, blogged of the Obama plan last February. “Last year the Congressional Budget Office estimated the president's proposal would raise $293 billion over 10 years.”

But here’s the bigger issue posed by what Romney floated—it contradicts the message that he would lower taxes on “job creators” who he claims would suffer under Obama’s proposal to let the lower tax rates first introduced by George W. Bush expire on families earning more than $250,000.

"Look, the American people ought to choose the course for the future. If they want to raise taxes on business creators and cause a further slowdown, why they can vote for President Obama," Romney told CNBC in July. "But if they want to see this economy roaring back with good jobs, they ought to vote for me in my view, and we ought to give whichever president is going to be elected at least six months or a year to get those policies in place."

His economics adviser Glenn Hubbard, a former Bush aide who is dean of Columbia University’s Business School, predicted in an August Wall Street Journal editorial that Romney’s plan—centered around tax reform—would increase GDP growth by as much as 1 percent annually for the next decade.

At least one prominent individual would likely feel some new financial pain if the proposal ever became policy—Romney. The co-founder of the private equity firm Bain Capital claimed $2.25 million in charitable deductions alone in his 2011 tax filing.

If those deductions were capped as he proposed, back of the envelope calculations indicate Romney would owe the government another $300,000 than the $1.95 million he paid.