For a country still gasping to recover from the Great Recession, disability payments from Social Security have evolved into a lifeline and an economic trap for millions of unemployed Americans threatening the program with insolvency in just four short years.

Created decades ago to help those unable to work because of severe health problems, the $128 billion program stops many from sliding into total poverty and inflicting further damage on the economy. More Americans qualified for disability than found jobs over the past three months, and since 2000, the number of beneficiaries rose by 73 percent, even though the workforce rose by less than 10 percent. But of the 8.7 million beneficiaries, federal officials claim the vast majority – with some estimates as high as 99 percent – will never rejoin the workforce and remain dependent on the federal government.

RELATED: Unemployed and Retired: You Too Can Double Dip

Both the Obama administration and congressional Republicans say that they are weighing reforms to salvage the finances of the disability system before the politics of the issue harden along partisan lines.

"It requires you to think very hard about the social contract for this program," said Janice Eberly, the assistant Treasury secretary for economic policy. "Working is preferred to any programmatic alternatives, both from the individual's view and the taxpayers' view."

Hints about what the reforms could look like appeared last week in a pair of reports by the Government Accountability Office and the Congressional Budget Office. The GAO indicated that the government could narrow the health eligibility standards for receiving disability. Guidelines for those suffering from mental disorders and muscle pain – about 67 percent of all beneficiaries – were last updated in 1985, shortly after Congress liberalized the screening process. Stricter criteria would limit enrollment and reduce the costs.

Separately, the CBO issued an analysis detailing potential savings of $22 billion in 2022 from reducing benefits across the board by 15 percent, eliminating disability payments for anyone older than 62 eligible for the Social Security retiree program, and raising additional tax revenue specifically for SSDI.

Another quick fix discussed by federal officials involves raising the share of Social Security tax revenues directed toward the disability program, although that would come at the expense of the portion of the trust fund for retirees already projected to reach insolvency by 2035.

"The growing number of people on disability and other federal benefits, combined with weak economic growth, raises serious concerns about the sustainability of the American economy," said Sen. Jeff Sessions, R-Ala., in response to the CBO report. "This program must be improved to avoid sinking our country deeper into debt, to ensure the program remains viable for those with disabilities, and to protect Social Security itself."

It will be several months before the tedious slog of reform begins in earnest. The legislative docket is already crowded with symbolic votes on taxes ahead of the November election, a stalled farm bill, and the steep fiscal cliff in the federal budget without congressional intervention.

"I plan on working with my subcommittee colleagues from both sides of the aisle to address program challenges early next Congress," said Rep. Sam Johnson, R-Texas, who as chairman of the Ways & Means subcommittee on Social Security will wrap-up a series of five hearings about the disability system in September. The congressman stressed in an email to The Fiscal Times that the hearings have "only strengthened my resolve to act as soon as possible to secure the future of this vital program."

Despite elements of bipartisanship, Obama has been battered outside the beltway over the issue. Gary Alexander, Pennsylvania’s secretary of Public Welfare, has circulated a PowerPoint slide claiming that 4.7 million workers have signed up for disability under the president’s watch. The Social Security Administration reports a significantly smaller, but meaningful, net increase of 1.23 million during the same period.

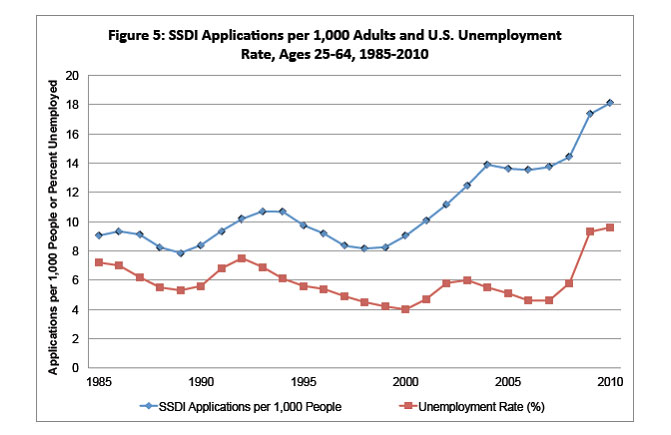

Well before the 2008 financial meltdown, disability claims were particularly sensitive to the economy. Applications – of which there were 13,000 a day last month –have moved in sync with employment, according to data tracked by MIT economist David Autor. Drops in energy prices, which often mean layoffs among miners, have previously led to a spike in applications from those living near Appalachian coal mines, according to a 2002 paper published in the American Economic Review.

"A person who ends up on disability insurance is usually there for the rest of their life," said University of Pennsylvania economist Mark Duggan, who has studied the program and proposed changes to make it financially sound. "It’s what economists call an ‘absorbing state,’ being on this program."

Addressing the quandary in a white paper last December, the Obama administration called for extending unemployment benefits this year to reduce the ranks of the jobless applying for disability. The paper drew on preliminary research by Alan Krueger, chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, showing that jobless Americans over the age of 50 with little savings increasingly apply for disability as their 99-weeks of unemployment runs out. SSDI continues until the beneficiary is old enough to collect Social Security.

For baby boomers that were laid-off on the cusp of retirement and are unable to land another job it’s naturally tempting to turn to disability benefits under the current system. But the cyclical nature of the increase in applications dovetails with the demographic trends of a graying population more likely to suffer from health problems and years of wage stagnation that make the relatively modest disability payment of $1,111 a month – slightly less than minimum wage – attractive to those with little earning power.

"This is in many ways a safety net for families," the Treasury Department's Eberly said. "These are often financially insecure households to begin with."

However, there is evidence from a 2010 GAO report about potential fraud in the program. Using data from 12 states, the watchdog agency found that 62,000 truckers received or renewed their commercial driver’s licenses after the Social Security Administration concluded that they were unable to work and qualified for full disability. It also discovered that 1,500 federal employees improperly received benefits.

Disability advocates oppose any efforts to limit the number of people eligible for disability or trim benefits, with groups such as the American Association of People with Disabilities and the National Organization of Social Security Claimants Representatives denying the program has evolved into a substitute for unemployment.

The previous government crackdown on disability payments during the 1980s led to a public uproar and changes to the medical standards that were scrutinized in the GAO report, said Ethel Zelenske, director of government affairs for the claimants organization.

"If you want to limit the amount of benefits paid, you can cut people off," she said. "That’s the one way to find savings fast – and I really don’t think it’s what most people, including members of Congress, want to do."