Fast-changing economic realities have a way of making presidential campaign rhetoric as ephemeral as Washington’s fading cherry tree blossoms.

That would appear to be the case this year with Republican soon-to-be standard-bearer Mitt Romney’s China policy. On the eve of a once-a-decade transition in the top ranks of its ruling Communist Party and the possibility of a political turnover in the U.S., China’s long-running and rapid economic expansion is showing distinct signs of aging.

Its growth rate is falling for the second straight year. The Asian Development Bank Institute this week predicted China’s economic growth would fall to 8.5 percent this year, down from 9.2 percent in 2011 and 10.4 percent in 2010. Inflation, meanwhile, is rising. And China’s trade and current account surpluses, which cause so much consternation in the U.S., are rapidly coming down.

These developments should come as no surprise. The Chinese currency (the renminbi or yuan) has been slowly appreciating in value for over half a decade, a move that has accelerated in the past 18 months under steady prodding from President Obama, who pledged to double exports during his time in office. A stronger currency makes China’s yuan-denominated exports more expensive and its dollar-denominated imports cheaper.

RELATED: China Reboot: From Textiles and Tea to High Tech

Meanwhile, the International Monetary Fund in its World Economic Outlook due next week is expected to show China’s current account surplus, which encompasses all financial transactions as well as trade, falling this year to 5 percent of gross domestic product, down from last fall’s projected 7 percent. A drop of that magnitude will make it much harder for China’s international trading partners to mount pressure for continued currency appreciation.

Indeed, there is an outside chance that as the U.S. moves through its election season, financial markets will begin gyrating to fears that China isn’t heading for a soft landing from its go-go years but is instead headed for a sharp slowdown in 2013. That would be a far greater threat to the U.S. economic recovery than China’s still large trade surpluses.

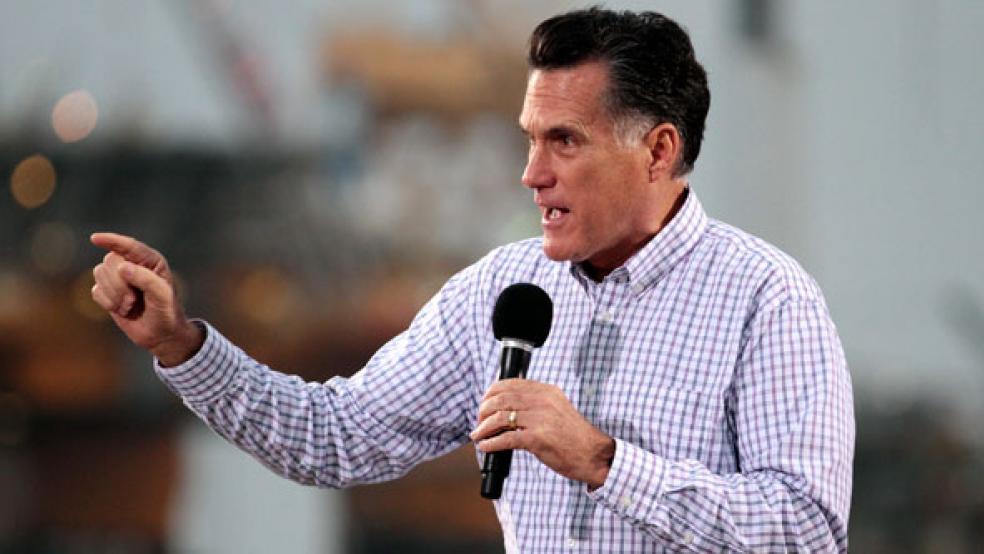

Those changing economic fortunes would seem to make the anti-China rhetoric emanating from Romney’s camp as antiquated as his support for the individual mandate in Massachusetts’ health care reform law. The former governor and private equity manager declared on a New Hampshire debate stage that on his first day in office he would declare China a currency manipulator, subject to international sanctions. “He wants to maximize the pressure,” Grant Aldonas, a top trade adviser who served in the Commerce Department under President George W. Bush, said in late March at forum on the future of U.S. manufacturing.

RELATED: Six Ways to Avoid an Economic Implosion in China

The rhetoric leaves some China experts scratching their heads. “Those arguments are substantially weaker than they were two or three years ago,” said Nicholas Lardy of the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “China’s currency is up 30 percent since 2005; it is much more determined by the market than it was before.”

And it leaves trade hawks wondering if Romney, with his Harvard Business School training and elite business background, is sincere. Virtually every top U.S. corporation belonging to the U.S.-China Business Council, which represents a broad cross section of the Fortune 500 ranging from Walmart to GE to Caterpillar, quietly applauds the administration’s refusal to brand China a currency manipulator in its biannual reports, the latest of which is due next week.

The late Steve Jobs, when asked by Obama if he could bring some of those jobs back to the U.S., said simply, “no."

They also soft pedal concerns about intellectual property theft to preserve access to the Chinese market. Many have set up major production platforms in China to both serve the local market and export to the U.S. and other countries.

Apple, for instance, whose reputation is under assault because of labor practices at its contractors in China, now gets nearly a third of its sales in Asia as compared to 38 percent in the Americas. The trend suggests those lines will soon cross. The late Steve Jobs, when asked by Obama if he could bring some of those jobs back to the U.S., said simply, “no.”

“Romney has been very tough on the currency thing, but given his background, you have to wonder if he means it,” said Clyde Prestowitz, president of the Economic Strategy Institute and author of “The Betrayal of American Prosperity.” A top trade official in the Reagan administration, Prestowitz’ long experience as a trade warrior tells him, “even though Americans are being hurt by trade, nobody pays attention except in election years.”

China is being portrayed as a rising geopolitical and military threat and a rival for hegemony along the Pacific Rim.

Domestic political considerations have often driven trade rhetoric, and China represents a far juicier target than Japan did in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the last time trade imbalances with the world’s then second largest economy became a hot-button issue. Then, as now, the Asian export power stood accused of engaging in predatory trade practices, stealing intellectual property and closing off its home market to U.S.-based firms. Then, as now, the Asian export power’s currency was deemed substantially undervalued.

But now, unlike then, China is being portrayed as a rising geopolitical and military threat and a rival for hegemony along the Pacific Rim. Japan was always a close political ally and provides a home for bases and ports that allow the U.S. to project its military might throughout the Asia-Pacific region.

Romney’s military strategy for the region dovetails with his trade rhetoric. It includes boosting Pentagon spending despite the U.S. government’s budgetary woes. He has promised a major shipbuilding program to counter China’s naval expansion and pledged to increase the U.S. aircraft carrier presence in the region, where China periodically spars with Vietnam, Taiwan and Japan over small, unpopulated islands in international waters.

The Chinese have heard get-tough rhetoric from presidential candidates before, and incumbents like Obama have often been accused of being soft on China’s policies on human rights, trade, Tibet or Taiwan. Kenneth Lieberthal, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who served the Clinton White House as a top Asia adviser, says that usually isn’t a problem since “if they win, they typically over a period of time end up basically adopting the policies of their predecessor and then building on that. The Chinese have heard this record before and know it well,” he said.

The problem comes when candidates get specific about what they plan to do “on day one,” as Clinton did before winning office by blasting the first Bush administration for being soft on China’s human rights violations. “If (Romney) does not declare China a currency manipulator on day one, some supporters on day two will ask him when he is going to fulfill his commitments,” he said. “This may be a smart electoral strategy, especially given the importance of the Midwest industrial states, but it is not a smart strategy in terms of how it positions him if he assumes office.”