When President Obama chastised Republicans and the court for challenging the consitutionality of the Affordable Care Act, he argued that overturning the law would be unprecedented, and that such an action would ultimately be the court thumbing its nose at Congress and the will of the people.

Obama said, "Ultimately, I'm confident that the Supreme Court will not take what would be an unprecedented, extraordinary step of overturning a law that was passed by a strong majority of a democratically elected Congress." After his scolding, legal scholars pounced, pointing out that the court has indeed overturned laws passed by Congress that are deemed unconstitutional, and that Obama, as a lawyer and former president of the Harvard Law Review, should have known better.

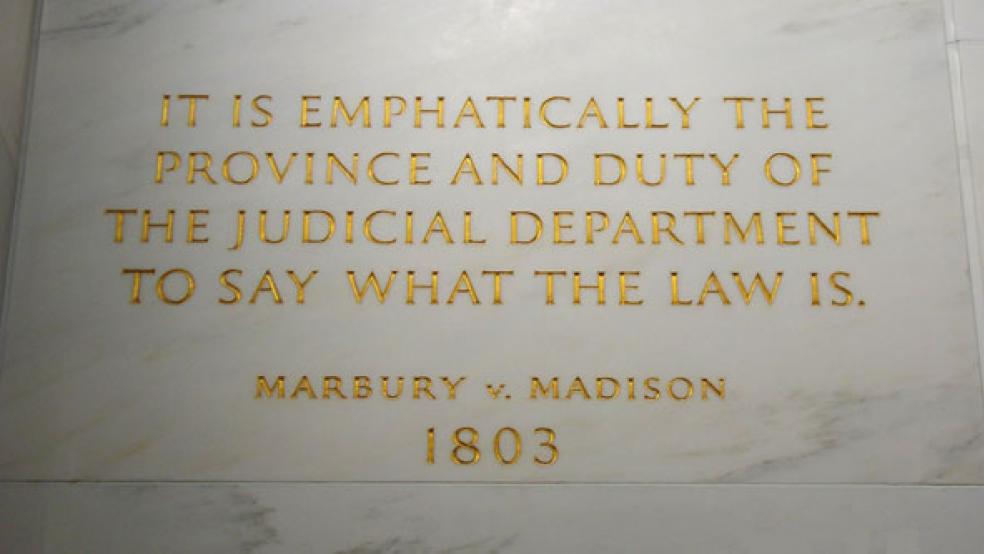

An editorial in the Wall Street Journal said, "President Obama ...famously taught constitutional law at the University of Chicago. But did he somehow not teach the historic case of Marbury v. Madison?" So here, for your edification, is a government document that explains the precedent-setting case:

MARBURY v. MADISON (1803)

Outgoing President John Adams had issued William Marbury a commission as justice of the peace, but the new Secretary of State, James Madison, refused to deliver it. Marbury then sued to obtain it. With his decision in Marbury v. Madison, Chief Justice John Marshall established the principle of judicial review, an important addition to the system of “checks and balances” created to prevent any one branch of the Federal Government from becoming too powerful. The document shown here bears the marks of the Capitol fire of 1898.

“A Law repugnant to the Constitution is void.” With these words written by Chief Justice Marshall, the Supreme Court for the first time declared unconstitutional a law passed by Congress and signed by the President. Nothing in the Constitution gave the Court this specific power. Marshall, however, believed that the Supreme Court should have a role equal to those of the other two branches of government.

When James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay wrote a defense of the Constitution in The Federalist, they explained their judgment that a strong national government must have built-in restraints: “You must first enable government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.” The writers of the Constitution had given the executive and legislative branches powers that would limit each other as well as the judiciary branch. The Constitution gave Congress the power to impeach and remove officials, including judges or the President himself. The President was given the veto power to restrain Congress and the authority to appoint members of the Supreme Court with the advice and consent of the Senate.

In this intricate system, the role of the Supreme Court had not been defined. It therefore fell to a strong Chief Justice like Marshall to complete the triangular structure of checks and balances by establishing the principle of judicial review. Although no other law was declared unconstitutional until the Dred Scott decision of 1857, the role of the Supreme Court to invalidate Federal and state laws that are contrary to the Constitution has never been seriously challenged.

“The Constitution of the United States,” said Woodrow Wilson, “was not made to fit us like a strait jacket. In its elasticity lies its chief greatness.” The often-praised wisdom of the authors of the Constitution consisted largely of their restraint. They resisted the temptation to write too many specifics into the basic document. They contented themselves with establishing a framework of government that included safeguards against the abuse of power. When the Marshall decision Marbury v. Madison completed the system of checks and balances, the United States had a government in which laws could be enacted, interpreted and executed to meet challenging circumstances.