Improper payments – to the wrong person, in the wrong amount, or for the wrong reason -- cost Medicare $48 billion last year, or nearly 10 percent of the $516 billion spent on care for seniors, according to federal estimates. And others suggest that the total number for Medicare fraud and waste is close to $100 billion a year.

Whatever the tally, the inability to stop the bleeding at Medicare represents another lost opportunity to wring substantial savings from the federal budget, and it puts additional pressure on Congress and President Obama to cut Medicare benefits as part of the effort to shrink the deficit by at least $1.2 trillion over the next decade.

Beyond that, the losses at Medicare call into question the efficacy of contracting with some of the nation’s largest insurance companies to process Medicare claims, spot suspicious billing, and refer cases to law enforcement.

The contractors are primarily subsidiaries of big health insurers, such as WellPoint and Blue Cross Blue Shield.

Government auditors have criticized these companies for poor performance in the past and faulted Medicare officials for not holding them accountable. A report last year by the Health and Human Services inspector general said one group of 18 contractors identified just $835 million in overpayments in 2007, and 16 of them referred $54 million or less for collection. Medicare is now consolidating that work in seven regional contracts. Overall, in the last fiscal year (2010), Medicare paid $956 million to these contractors for claims processing and fraud detection, according to government figures.

The contractors generally get paid regardless of what they find, although Medicare has been expanding its use of “recovery audit contractors,” which collect up to 12.5 percent of the improper payments they uncover. Overall, Medicare says in its latest budget request, the return on investment from its “program integrity” work is 14 to 1. But the Government Accountability Office says the agency’s calculations are flawed because they don’t include contractors’ expenditures beyond the end of a fiscal year. In response to a July audit, Medicare pledged to make changes.

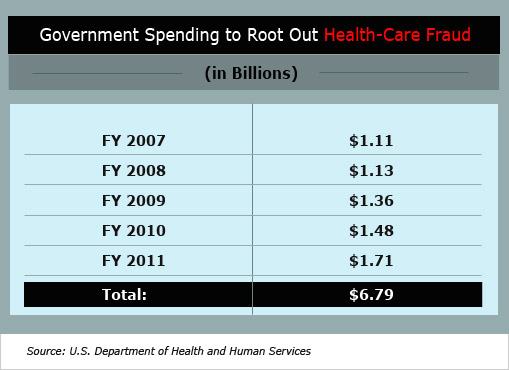

Since 2009, Medicare officials say, they have taken extraordinary steps to prevent and prosecute fraud by screening new providers more rigorously and deploying the types of technology used for years in the credit-card industry. Federal spending on the fight against health-care fraud, waste, and abuse has jumped 54 percent since 2007 to $1.7 billion.

The Obama administration has also trimmed the number of contractors and granted them broader powers to identify problems across multiple providers and benefit types. Meantime, in response to a request earlier this year from three U.S. senators, the Health and Human Services inspector general is examining contractor performance, whether contractors have disclosed their conflicts of interest, and how Medicare is addressing those potential conflicts.

In April, for example, Medicare awarded a $68 million contract to Cahaba Safeguard Administrators, a unit of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Alabama, to help find fraud in the massive health-care program. A month later, the government quietly put the contract on hold amid allegations that the company had conflicts of interest that would impair its ability to protect taxpayer dollars.

“We need a thorough examination of relationships between the contractors paying Medicare claims and their related corporate entities…to make sure taxpayer dollars aren’t being wasted,” Senate Finance Chairman Max Baucus, D-Mont., said in March.

Tony Salters, a spokesman for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which oversees both programs, says the agency shares the senators’ concerns that contractors must be free from conflicts of interest and it began onsite performance evaluations of its anti-fraud contractors in May after a four-year hiatus.

Still, the recent case of Cahaba is emblematic of the conflicts that can arise. In April, Cahaba was awarded the $68 million contract covering seven Midwestern states. Government officials halted the contract on May 16 after receiving a protest from a rival bidder, according to a spokesman for the GAO, which handles contract appeals.

According to a copy of the bid protest shared with The Fiscal Times, Cahaba could have been responsible for reviewing its own work as a claims processor and investigating its parent company’s Medicare Advantage and Part D prescription-drug plans. Blue Cross of Alabama is also part-owner of Prime Therapeutics, the country’s largest privately held pharmacy-benefit manager, serving 17 million consumers. The work on this contract “can directly affect Cahaba’s and its affiliates’ revenue and profits,” attorneys for AdvanceMed, another Medicare contractor, wrote in the bid protest.

Cahaba also provides auditing and consulting services to Medicare providers. Koko Mackin, a spokeswoman for Cahaba, declined to comment and referred questions to Medicare. Salters, the Medicare spokesman, says the existence of overlapping government contracts doesn’t necessarily pose a conflict. He says Medicare is more concerned if a company affiliated with the contractor is submitting claims.

Medicare raised that issue last year with Palmetto Government Benefit Administrators, a unit of Blue Cross Blue Shield of South Carolina in Columbia, S.C. In April 2010, according to GAO records, a CMS contracting officer concluded Palmetto had a conflict since its parent company operated medical clinics that would submit claims to Palmetto for payment and review. Medicare initially rejected Palmetto’s proposal to hire an independent auditor for those claims to avoid the conflict. Later, Medicare determined the conflict wasn’t significant and granted Palmetto a waiver without requiring any “avoidance/mitigation strategies,” GAO documents show. Billy Quarles, a spokesman for Palmetto, says the company “reviews and pays claims in line with applicable law, regulations and CMS instructions.” He referred further questions to Medicare.

Also last year, the GAO upheld a bid protest against AdvanceMed because its regional contract would force it to review the work of its then-parent company, Computer Sciences Corp., on Medicare prescription-drug plans. In April, Computer Sciences sold AdvanceMed to NCI Inc. of Reston, Va., to eliminate the conflict. Representatives for AdvanceMed couldn’t be reached for comment.

Officials at WellPoint, the nation’s largest insurer with 34 million members, say they go to great lengths to avoid conflicts. WellPoint offers Medicare Advantage and prescription-drug plans while also serving as a Medicare claims contractor. In June, National Government Services, a WellPoint unit, joined with Northrop Grumman and Verizon to win a $77 million contract for a new computer system that allows Medicare for the first time to flag suspicious claims nationwide before they’re paid. “We have so many firewalls and different external audits that take place to monitor and prevent conflicts of interest from becoming a larger issue,” said Mary Ludden, director of program integrity at NGS.

At a Sept. 13 hearing of the deficit-reduction Super Committee, several lawmakers singled out Medicare’s wasteful spending as one way to save a significant sum without gutting popular entitlements. “We can save on Medicare without cutting benefits,” Sen. Jon Kyl, R-Arizona, said, citing a Cato Institute study on fraud and waste.

Malcolm K. Sparrow, a professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government and author of License to Steal: How Fraud Bleeds America’s Health Care System, says it’s wishful thinking by politicians to assume billions of dollars can be recouped under the current Medicare structure. “The yard has already been overrun by a pack of marauding dogs,” he says, “and they are eating us up.”