It’s a refrain we’ve all heard many times before: Small businesses are the engine of job creation in America. Small Business is the engine of job creation in America, right? We’ve heard that over and over again from politic ians on both sides of the aisle. At one of the stops on his three-day, three-city bus tour last week, President Obama took to the stage to talk about the importance of small businesses in getting the economy back on track. “We genuinely believe that small business is the backbone of America. It’s going to be the key for us to be able to put a lot of folks back to work,” Obama said.

The trouble is, small business’s role as the star of job creation is not completely accurate. It’s true that small businesses—defined generously as companies with fewer than 500 employees—account for more than half of all private-sector employment, but the repeated emphasis on those businesses may overshadow some broader truths about the job market. Small businesses do create the most jobs overall, but as the businesses shrink or die off, they also eliminate the most jobs, leaving little net gain. And while the Small Business Administration says companies with fewer than 500 employees have generated nearly two-thirds of all net new jobs over the last 15 years, economists who sliced the jobs data differently reported in an August 2010 paper that the size of businesses doesn’t really matter when it comes to adding jobs — but their age does.

“The only group that disproportionately creates jobs is startups,” says Ron Jarmin, assistant director for research and methodology at the U.S. Census Bureau and coauthor of that research paper, titled “Who Creates Jobs? Small vs. Large Vs. Young.”

Startups account for only about 3 percent of U.S. employment, but they account for nearly 20 percent of the gross number of jobs created year to year, according to Jarmin and his coauthors. And the net new jobs from startups can be credited for all the job growth in the U.S. over a stretch of roughly three decades starting in the late 1970s, according to Robert Litan, vice president for research and policy at the Kauffman Foundation, which promotes entrepreneurship. That’s because while other businesses both create jobs and destroy them as they grow and shrink in a changing economy, startups by definition only add workers initially.

Many of those startups will fail, of course, and kill off jobs in the process, but some new businesses that survive also go on to thrive and grow—think Google, Facebook, or Groupon—rapidly adding lots of employees. That historic importance of young businesses may be why Obama made a point of specifically mentioning startups along with small businesses his remarks last week.

Now with the economy still struggling to dodge a double-dip recession and with the unemployment rate hovering stubbornly above 9 percent, it’s clear that mass layoffs at large companies have taken a significant toll. But a sputtering job-creation engine at startups has also played a large part. So as the president gets set to make a post-Labor Day announcement about initiatives intended to boost employment, a slew of other data suggest he’ll need to confront some troubling trends that indicate a broader decline in American entrepreneurship.

The Kauffman Foundation highlighted three negative developments in a report released last month: Fewer new companies are being born, they’re hiring fewer employees, and they are dying off faster than they had in the past.

“The United States appears to be suffering from a long-term leak in job creation that pre-dates the recession and has the potential to persist for an unknown time,” Litan and E.J. Reedy wrote in the report. “The heart of the problem is a pullback by newly created businesses, the economy’s most critical source of job creation, which are generating substantially fewer jobs than one would expect based on past experience.”

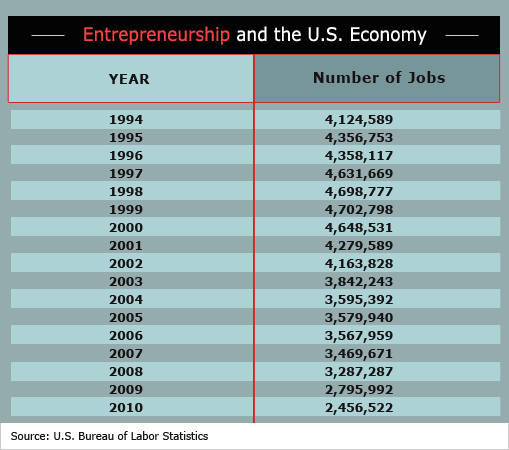

The number of new establishments rises and falls with the economy, but has been in decline in recent years. The Bureau of Labor Statistics says that, after climbing through the late ‘90s, the number of new businesses in the year ending March 2010 was lower than in any other year since 1994, when the agency began tracking such data. The 12 months ending in March 2010 had 505,000 businesses less than one year old, off from a peak of 667,000 in 2006 and lower than the 550,000 in existence in 1993-4 (see chart below).

The number of jobs created by companies less than a year old has fallen from 4.1 million in 1994 to 2.5 million in 2010, according to BLS data. A drop in so-called “employer startups”—those that are bigger than just one person hanging a shingle—is a key factor in the decline. Since 2006, the number of those types of businesses being formed each year has fallen 27 percent.

Startups have been opening for business with 4.9 employees, on average, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, down from about 7.5 for much of the 1990s.

So while startups had accounted for around 3 million net new jobs a year prior to the Great Recession, reaching a peak near 3.5 million in 2006, that number has dropped off steadily since then. By 2009, jobs created by startups had slid to 2.3 million. “That’s like a canary in a coal mine,” says Litan. Since some of those jobs will be lost as some upstart companies falter, the businesses created in 2009 will likely never account for more than that number. And the total shortfall in net jobs created by startups since 2005 is more than 2 million jobs, Litan says.

“That doesn’t explain, of course, the mass unemployment we’ve got, which is something like 8 million jobs,” Litan says. “But 2 million of that 8 million is probably due to this decline in the startup engine.”

The five-year survival rate for startups, surprisingly high at around 50 percent through much of the 1990s, has also edged lower in recent years, dipping below 45 percent. And of course, as those businesses fail, the jobs they had created disappear.

The recession can’t be blamed for all of that damage—some of these trends date back to 2005, before the downturn was under way. “Even before the Great Recession, firms were starting smaller,” Reedy and Litan write. “They were opening their doors with fewer workers than the historic norm and were relatively reluctant to expand their workforces even during good economic times. Since at least the middle of the last decade and perhaps earlier, the growth trajectories and survival rates for these businesses meant that they were contributing fewer and fewer new jobs to the economy.” Those trends did, however, accelerate as the economy began to contract.

Economists aren’t sure yet what prompted those pre-recession declines. “I don’t think we have a good explanation for that,” the Census Bureau’s Jarmin says. Productivity gains driven in large part by new technology likely play a big part. It may also be that, as the economy continues to shift away from manufacturing, the types of businesses being started are different than in the past. Litan also points to the rise of the freelance economy, in which businesses outsource tasks that they might have tasked employees with in the past. These days, “it’s a lot easier to outsource it and hire somebody on a contract basis for something very specific,” he notes. “Then turn it off and hire somebody else to do something else.”

To counteract the slowdown in startups, the Kauffman Foundation last month proposed a package of legislation meant to increase the number of high-growth new businesses. Kauffman’s “Startup Act” includes suggestions for immigration reform intended to lure entrepreneurs from abroad—particularly those with degrees in science, technology, engineering and math—to build their companies here. The proposal also includes provisions to streamline regulation, improve access to early financing and overhaul the patent process. “We know that many of these proposals are controversial,” Litan told The Fiscal Times. But the foundation hopes that by packaging them in a bill designed to spur job creation, lawmakers will be willing to give them a fresh look.

If that sounds like a tall order, Scott Shane, a professor of entrepreneurship at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, injects a couple of other notes of caution about the effectiveness of focusing on startups. “This big illusion that policymakers have is this belief somehow that boosting startups will be a big answer to the employment problem,” he says. “Certainly, anybody creating jobs is going to help the employment problem, but you can’t do it off startups alone. The numbers don’t work.”

Startups, after all, still represent some 3 percent of private-sector jobs—so even boosting their job-creating power significantly may not accomplish all that much. Plus, says Shane, jobs at startups tend to be less rewarding than those at large and mature firms. “The average wage is lower, benefits tend to be worse, and the stability of the job—the permanency of employment in those companies—tends to be lower, not because they tend to lay off more people but because they go under and take the jobs with them,” he notes.

In the end, Shane suggests, the best approach may be for policymakers to look for ways to increase hiring—and decrease job destruction, whether it be through layoffs or other means—across a wider spectrum of businesses. “If we’re just talking about giving an incentive for businesses to hire, why don’t we just give them all the incentive? Why does it matter that they’re small or new or old and large?”