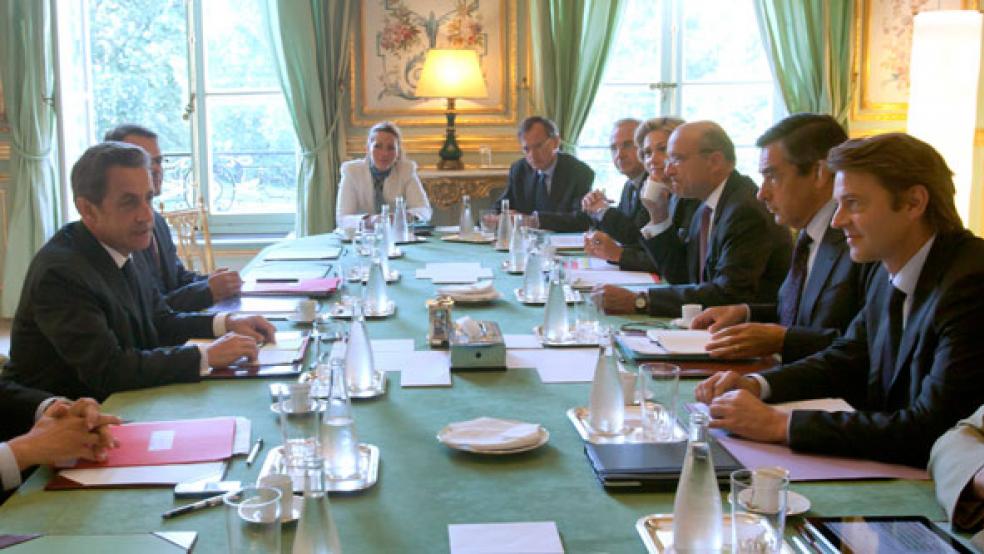

Concern that France’s AAA bond rating might be downgraded began to abate Thursday, after French President Nicolas Sarkozy rushed back from the French Riviera for an emergency cabinet meeting and the European Central Bank provided overnight lending. The action gave a needed jolt to U.S. markets, with Dow regaining most of yesterday's losses, closing up 423 points.

But Paris is not out of the woods yet in escaping the same kind of Standard & Poor’s downgrade that sent the U.S. economy reeling. The country’s debt trajectory may not be sustainable. And the underlying well-being of the French financial system remains highly suspect.

None of this is new, of course. In April, before she became managing director of the International Monetary Fund, Christine LaGarde, then minister of economic affairs in the French government, told The Fiscal Times, “I am told they [French banks] are safe.” Hardly a ringing endorsement. Such doubt sows fears that threats to the financial health of banks could reemerge at any time.

France is not Italy in terms of debt or the probability of default. France’s debt to GDP ratio is expected to be 87% in 2012, while Italy’s ratio will be 119%. Nevertheless, as measured by the cost of insuring against a default, -- the likelihood of Paris getting in trouble has doubled in just the last year.

Much of the rising concern reflects uncertainty about the ability of the French financial system to withstand a potential Italian default. As of the end of March 2011, French banks held $410 billion of Italian debt, by virtue of their holdings of Italian government bonds and loans to the private sector, according to the Bank for International Settlement. They were also on the hook for $86 billion because of credit commitments, derivatives contracts and other loan guarantees in Italy.

The ability of the French financial system to weather an Italian storm is doubtful because French banks are less capitalized than their major European counterparts. Such concerns prompted the International Monetary Fund, in its 2011 assessment of the French economy, to warn against “downside risks.” The opaqueness of the French financial system only compounds this problem.

The Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperationand Development, in its 2011 economic survey of France, complained that it was “difficult to assess” the banks’ strength because the French government does not publish details about the financial sector’s health.

This lack of transparency has fed financial market jitters and public distrust. Only 17% of the French have confidence in the banks to avoid a new financial crisis, according to a Harris interactive poll of 1,090 individuals in France released August 11.

“I am not saying there are skeletons in the cupboard,” said Nicolas Veron, a senior fellow at Bruegel, a Brussels-based think tank. “But if there were, there would be very little way for the outside world to hear the bones rattling.”

If there are skeletons, the implications could be profound. A downgrading of France’s bond rating would slow French economic growth, imperiling prospects for a European economic recovery. France is also the second largest guarantor of the Economic Financial Stability Facility, which uses the AAA bond rating of France and others to raise money in financial markets that it has used to bail out Greece, Ireland and Portugal. Any French downgrade would place more of the cost for such rescue efforts on a reluctant Germany.

Bruce Stokes Is Senior Transatlantic Fellow for Economics with the German Marshall Fund of the United States