On a wintry mid-March afternoon at a sparsely attended meeting of a House Financial Services subcommittee, a handful of legislators heard testimony on five bills that would repeal or replace parts of last year’s sweeping financial services reform legislation, better known as Dodd-Frank after its chief congressional sponsors. Each bill had a different goal: One would release some derivatives transactions from margin rules; one would exempt private equity advisers from registration requirements; another would void an executive compensation disclosure regulation contained in the new law.

The commonality among the five bills? They were all sponsored by freshman Republican legislators holding coveted committee spots, who were showered with campaign donations from financial industry groups immediately after the November elections, according to an analysis by The Fiscal Times and the Center for Responsive Politics.

The freshmen – Steve Stivers of Ohio, Robert Hurt of Virginia, Michael Grimm and Nan Hayworth of New York, and David Schweikert of Arizona -- all hail from swing districts. Each won with 54 percent of the vote or less and will likely face tough reelection battles in 2012 when Republicans seek to maintain control of the House.

Long-time Republican operatives say freshmen legislators with scant legislative experience were anointed by GOP leaders and wound up sponsoring bills that would clearly benefit the bottom lines of firms in the financial services industry.

“It’s orchestrated. The leadership is trying to take care of them,” said Ed Rollins, a Republican campaign consultant at The Dilenschneider Group, who rose to national prominence during the Reagan years and most recently ran former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee’s 2008 presidential campaign. “A lot of that bill isn’t popular, and it’s a good way to get close to people who want it repealed.” As expected, both legislators and industry representatives deny any connection between the money and legislative outcomes.

always flowed most generously to members of

committees that consider legislation or regulatory issues.

The sizeable financial industry PAC contributions – Stivers alone raised at least $220,500 since the Nov. 2 election with nearly half coming from the finance, insurance and real estate industries known as FIRE –also illustrate how campaign contributions buy access to senior as well as junior members of key committees. Campaign finance experts say that donations by PACs and individuals associated with special interests have always flowed most generously to members of committees that consider legislation or regulatory issues germane to their interests.

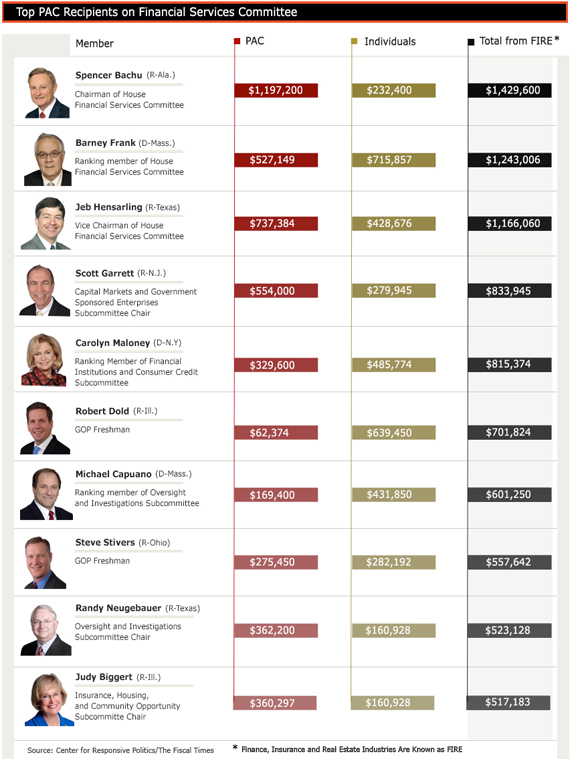

The new chairman, Rep. Spencer Bachus, R-Ala., an avowed critic of Dodd-Frank, took in more than $1.4 million in FIRE-related contributions to his personal and leadership campaign committees over the past two years, with 84 percent of it coming from industry PACs. It was the most of any member of the committee. Yet Rep. Barney Frank, D- Mass., one of the main architects of the legislation spawned by the 2008 financial meltdown, also used his campaign and leadership committees as magnets for financial sector PAC money. He brought in $1.25 million in FIRE-related donations, with 42.4 percent from PACs and 57.6 percent from individuals working in financial services.

Other top-ranking legislators on the committee pulling in more than $600,000 for their campaign and leadership committees during the 2010 election cycle from FIRE-affiliated PACs and individuals included capital markets subcommittee chairman Scott Garrett, R-N.J., and Jeb Hensarling, R-Tex., a fifth-term legislator who also chairs the House Republican Conference. Carolyn Maloney, D-N.Y., and Michael Capuano, D-Mass., the ranking minority members on the financial institutions and oversight and investigations subcommittees, respectively, also pulled in more than $600,000 from companies and employees from industries that their subcommittees oversee. (See chart for top ten FIRE recipients.)

Any suggestion that bill sponsorship is related to campaign finance is flatly rejected by the legislators. Stivers, for instance, said through a spokeswoman that he “is influenced by the people of Ohio’s 15th Congressional District” and that he is “focused on creating jobs and improving the economy in the district.” The banking industry, which has fared poorly in public opinion polls in the wake of the financial crisis and recession, denies their campaign contributions can buy votes or get bills introduced or passed. Their donations only give them access so they can voice their concerns about pressing economic matters. “We believe that it is our responsibility to participate in the political process to ensure that we protect our shareholders’ investment in our firm,” Goldman Sachs says in its annual report to stockholders.

on lobbying in the fourth quarter of last

year in addition to its campaign contributions.

The politically influential investment bank spent more than $1 million on lobbying in the fourth quarter of last year in addition to its campaign contributions. Since the last election, it has stepped up its contributions to freshman Republican legislators in particular, giving at least $8,000 to Stivers, $6,000 to Hayworth, and $1,000 to Grimm. The average member of the Financial Services Committee received more than three quarters as much in contributions from industries under their jurisdiction than the average member of Congress.

The Law that Tipped the Scales

In July 2010, Congress passed a major financial services reform bill, co-sponsored by Frank and Sen. Chris Dodd, D-Conn., that imposed a sweeping overhaul of banking regulations and numerous new disclosure requirements on corporate America and derivatives traders. Almost immediately, the affected industries attempted to water down the new rules by paying millions of dollars to lobbyists, many of whom previously worked on the Hill either as legislators or as staff to key committees, to pressure agencies such as the Treasury Department, the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, which are writing the new rules.

But with Republicans now in control of the House, the groups affected by the bill are also mounting a campaign to pass legislation that would either eliminate or dilute key provisions and funneling campaign contributions to the key legislators on the committee, including the dozen Republican freshmen, many of whom scored surprising upsets and received minimal contributions from the sector prior to the election.

- Grimm, 41, a Tea Party-backed candidate who entered politics after working as an undercover FB I agent exposing financial fraud, narrowly won his Staten Island seat despite being heavily outspent by incumbent Democrat Michael McMahon. During the race, just 25 percent of Grimm’s $1.3 million in contributions came from people or PACs associated with the finance, insurance or real estate industries compared to 20 percent of McMahon’s $2.7 million. Since the election, however, Grimm has raised 61 percent of the donations reported through the end of February from financial PACs with major donations coming from Goldman Sachs ($6,000), the American Bankers Association ($5,000) and the Investment Company Institute ($3,000), which represents the mutual fund industry.

- Stivers, a 46-year-old stock broker turned career politician from the Columbus, Ohio, suburbs, was a one-man financial juggernaut in the 2009-2010 election cycle, raising $2.7 million for his successful campaign to unseat Democratic incumbent Mary Jo Kilroy, who raised a similar amount. During the race, only 19 percent of his contributions came from individuals and political action committees associated with FIRE firms compared to less than 6 percent for Kilroy. In the first two months of this year, according to FEC filings, 85 percent of Stivers' $92,000 in receipts came from FIRE political action committees, including $5,000 from the Investment Company Institute and $4,000 from PricewaterhouseCoopers.

- South central Virginian Robert Hurt, a 41-year-old lawyer and state legislator, narrowly defeated incumbent Democrat Tom Perriello with 51 percent of the vote despite being outspent $3.8 million to $2.5 million. Neither man in the largely rural district received much from financial service firms during the race – about 10 percent for Republican Hurt compared to 6 percent for Perriello. In the four months after Election Day, however, a third of Hurt’s nearly $100,000 in PAC contributions reported thus far came from FIRE firms or trade groups, including $5,000 from the National Association of Realtors, $3,000 from the Independent Community Bankers and $2,500 from the American Bankers Association.

During the March hearing, which was heavily stacked with industry witnesses favoring the bills, each sponsor used very similar language to describe why the bill was important to their constituents. Requiring registration of advisers to private equity funds that provide capital to “struggling companies” will “impose an undue burden on small and mid-sized private equity firms and decrease capital available for job growth,” said Hurt, who sponsored the bill exempting them from that requirement in Dodd-Frank.

Damon Silver, a lawyer for the AFL-CIO, called Hurt’s bill the “no accountability for leveraged buyout funds act.”

The sole opponent invited to the hearing, Damon Silver, a lawyer for the AFL-CIO and a member of the congressional oversight panel for the Toxic Assets Relief Program, offered a caustic rebuttal in his testimony. He called Hurt’s bill the “no accountability for leveraged buyout funds act.”

Nan Hayworth, a physician representing well-off Westchester, Putnam and Orange counties north of New York City, sponsored the legislation repealing the requirement that publicly-traded companies include a salary comparison between top officers and average employees. “This bill eliminates irrelevant and confusing disclosure information . . . that diverts resources from job creation,” she said. Silver referred to it as the “promote CEO pay secrecy act.”

Grimm, who is sponsoring legislation that could exempt from Dodd-Frank’s new margin requirements two-party derivative transactions between highly regulated banks and firms that hedge currency and interest rate risk in their normal course of business, also sounded the jobs theme.

“We all want to create jobs. There was a meltdown. A lot of regulations weren’t enforced. There was a lack of oversight,” he said. But “the pendulum has swung so far that we could be over-regulating industry.”

Grimm’s bill should be called the “help create another AIG act,” Silver said.

Second Round Fund-Raising

Grimm has been particularly active on the money-raising front since the last election. He has held at least six fundraisers, according to the Sunlight Foundation, which keeps track of fundraising invitations. At an early February outing dubbed “Festa di compleanno” at Carmine’s just off Capitol Hill, a Washington outpost of the well-known New York City eatery, the suggested contributions for his birthday celebration were $2,500 to co-host; $1,000 for PACs; and $500 for individuals.

The monthly corporate PAC filings with the Federal Election Commission contained no individual donations from the intimate dinner, which a restaurant staffer said was held in a private dining room near the main bar, a room with its own overhead TV screen and lined with expensive bottles of wine. PAC contributions reported so far for that day included $1,000 from Goldman Sachs, KMPG Partners, PricewaterhouseCoopers and the National Association of Insurance and Financial Advisors.

Grimm, a former Marine who served in the first Iraq war, has been tapped as a future leader in the Republican Party. He’s one of 12 regional co-chairs for the National Republican Congressional Committee responsible for helping candidates throughout the Northeast in the next election.

While New York City would seem to be ripe territory for an adroit Wall Street fundraiser, the role is somewhat at odds with Grimm’s experience prior to entering politics. In 2002, Grimm went underground for nearly two years as a hedge fund manager in an FBI sting dubbed Operation Wooden Nickel. The Commodity Futures Trading Commission and the Securities and Exchange Commission eventually brought civil charges against at least 15 hedge fund operators for engaging in fraud and receiving ill-gotten gains from the sale of foreign exchange derivatives, which in some circumstances could become exempt from margin requirements should Grimm’s proposed bill become law.

Related Links:

Alabama Lawmaker Takes Aim at Financial Regulation Reforms (Center for Public Integrity)

Crisis Panel: Are there Still Banks Too Big to Fail? (The Fiscal Times)

Business Groups Seek Swap Exemption (The Fiscal Times)