There was a time when the Senate stood alone as the grown-up on Capitol Hill. A hastily passed House plan to completely overhaul the US healthcare system was going nowhere in the upper chamber, lawmakers assured the public. The Senate would start from scratch, producing its own version of a healthcare reform bill that would avoid some of the more obvious downsides of the House version, like an additional 23 million people without coverage after a decade and absurdly high premium increases for poor adults.

That was then. In the middle of last week, with most of the nation’s attention focused on former Federal Bureau of Investigation Director James Comey’s testimony about his meetings with Donald Trump, Senate leadership used a bit of procedural sleight-of-hand to place the American Health Care Act on the Senate calendar.

Related: Why a Top Republican Wants to Keep Paying the Obamacare Insurers

That makes it available for a floor vote without any referrals to committees with jurisdiction over the issues it raises. The goal of the Senate is to consider it as part of a budget reconciliation process that is immune to the filibuster and can be passed with only 50 votes plus a tiebreaker cast by Vice President Mike Pence.

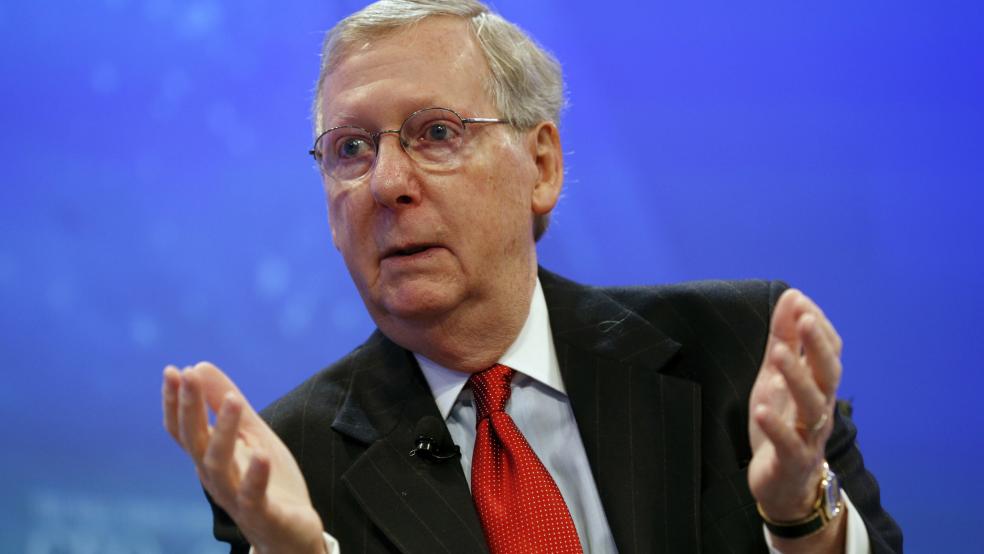

To make that happen, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell invoked the body’s Rule XIV, which creates the somewhat absurd mechanism for moving a bill directly to the floor. It requires a senator demanding that the bill is “read” twice on the Senate floor -- something that can involve as little as the Clerk of the Senate reading the bill’s title out loud -- and then objecting to further action on it, which includes a referral to one or more committees.

In a description of how the process works, the Congressional Research Service quotes a passage from a 2014 floor proceeding in which Democratic Sen. Sherrod Brown began the process of forcing a measure onto the calendar by objecting to his own motion.

Mr. BROWN: Mr. President, I understand that S. 2262, introduced earlier today by Senators Shaheen, Portman, and others[,] is at the desk, and I ask for its first reading.

The PRESIDING OFFICER: The clerk will read the bill by title for the first time.

The assistant legislative clerk read as follows: A bill (S. 2262) to promote energy savings in residential buildings and industry, and for other purposes.

Mr. BROWN: Mr. President, I ask for its second reading and object to my own request.

The PRESIDING OFFICER: Objection is heard. The bill will be read for a second time on the next legislative day.

Related: Senate Republicans Are Headed for a July 4th Showdown Over Health Care

But ridiculous procedure aside, the move by Senate Republicans to bring the extraordinarily unpopular AHCA to the floor without so much as a committee hearing is a remarkable one for several reasons.

First, as Democratic Sen. Claire McCaskill said in an eruption during a Senate Finance Committee hearing last week, it bypasses the sort of consideration any major piece of legislation is expected to receive in a chamber that styles itself “the world’s greatest deliberative body.”

“We have no idea what’s being proposed,” she said. “There’s a group of guys in a back room somewhere that are making these decisions. … We’re not even going to have a hearing on a bill that impacts one-sixth of our economy. … It is all being done with an eye to trying to get it by with 50 votes and the vice president.”

The “group of guys in a back room” McCaskill refers to is a team of 13 Republican senators -- all men -- who were given the task of crafting a Senate health care bill. Whatever they have produced is so far a mystery, which adds to the strangeness of McConnell’s move.

Related: GOP Plan for Expanded Medicaid Recipients Delays the Inevitable

There are different ways this could play out, but McConnell has said that the end game involves a vote by the end of June.

McConnell, as the rules allow, could bring up the House-passed AHCA on the Senate floor and try to pass it. This is risky at best. The bill is deeply unpopular, even among Republican voters, and with a 52-48 majority, McConnell can only lose two of his votes and still pass the bill. GOP senators from states that accepted the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion, which would go away under the AHCA, are going to have a hard time supporting it.

Another option is to bring the House-passed bill up for consideration on the floor, and then attempt to replace it, in whole or in part, through amendments that reflect whatever decisions have been made by the Senate’s secretive health care working group. This is also risky because many members won’t have had much time to review the legislation before being asked to vote on it, and given its extensive impact on the economy, some might balk.

It’s also possible that by conducting their negotiations in secret, the members of the working group don’t have a good grip on the support that any replacement measure could command among GOP senators. As the House fight over the AHCA proved, striking a balance between the party’s hard right members and its more moderate one is an extremely tricky feat.

It’s always a mistake to underestimate McConnell’s ability to make things happen in the chamber he’s occupied for decades, but the task he’s set for himself over the next few weeks looks like a heavy lift, even for him.