Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to the United States could have come at a better time, at least from the perspective of those looking at the Chinese economy. Had Xi arrived a year ago, he’d have done so at the helm of a country expanding prodigiously through trade and investment while slowly opening its markets to global companies all but begging for access to its growing middle class.

What a difference a year makes. These days, just about the only person warning about China’s economic dominance is billionaire presidential candidate Donald Trump, who constantly complains that China is “eating our lunch” in global trade.

Related: The Pope Was a Breeze for Obama…China’s President Xi Is Another Story

The Chinese economic model “has run out of steam, former Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson told CNBC earlier this week.”The only way to have real competition that's going to benefit the Chinese economy is to open up to foreign competition so you have the best businesses and the most efficient businesses competing there.”

Now though, Xi is being forced to confront business leaders who are a little more wary about getting involved in China than they’ve been in the past.

They have watched Chinese manufacturing activity drop to levels not seen in nearly seven years.

Xi began his trip to the U.S. on the West Coast, where on Tuesday he had to defend the growth prospects of the Chinese economy before an audience of business leaders. They have watched Chinese manufacturing activity drop to levels not seen in nearly seven years, even as the country’s nascent stock market continues to writhe from the aftereffects of the recent crash that sent shockwaves around the globe.

“Our economy is under pressure but that is part of the path on the way toward growth,” Xi told the group.

Related: Why U.S. Investors Shouldn’t Be So Worried About China

That same day, however, the Asian Development Bank released its latest estimate of Chinese GDP growth for 2015 and 2016, and the news was not good. The bank cut its growth estimate from 7.2 percent to 6.8 percent for 2015, and from 7.0 percent to 6.7 percent for 2016.

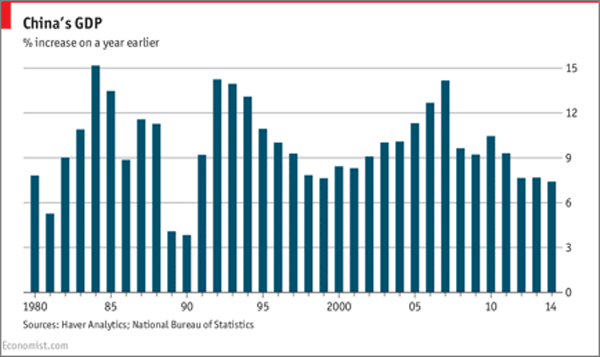

While these numbers remain high relative to growth rates in developed countries, they represent a real decline in China, where the booming economy, just five years ago, was growing at more than 10 percent per year.

To be sure, China’s long-term growth prospects are still very positive – something the Asian Development Bank remarked on even as it cuts its GDP estimates for this year and next.

“In addition to less favorable demographics and higher wage costs, the PRC’s adjustment to a new growth model that is based more on innovation, consumption, and services will bring with it more moderate growth,” ADB Chief Economist Shang-Jin Wei said in a press release. “As long as the country continues to pursue pro-market reforms, there is a good chance for the PRC to realize productivity gains and relatively strong future growth rates.”

Related: China v. Yellen – 3 Scenarios that Will Determine the Fate of the Global Economy

However, as recent events in the country have made clear, China’s journey toward a modern, market-based economy is unlikely to follow a smooth path.

The Chinese government made rising share prices a point of national pride, and encouraged investors to pour money into the market.

The recent travails of the country’s stock market are instructive. The country’s communist government, perhaps not surprisingly, seems to have been unfamiliar with the “market” element of the stock market. Rather than allowing the markets to decide for themselves whether companies listed on the exchange were worth investing in, the Chinese government made rising share prices a point of national pride, and encouraged investors to pour money into the market, artificially inflating a bubble and removing, in large part, the skepticism and due diligence necessary for a smoothly functioning system.

The result was the August crash that combined with the government’s ham-handed attempts to stabilize the situation – including forcing large shareholders in public companies to retain their holdings for a minimum of six months – kept global markets on a roller coaster for more than a month.

Related: 3 Major Lessons from the China Crisis that Wasn’t

In addition to the ban on selling shares, the government also devalued the renminbi, China’s currency, and slashed reserve requirements at banks. The combined and ineffective efforts to stop the bleeding in the markets made global investors nervous for two reasons.

First, it looked as though the government didn’t really have control over its economy. Second, it signaled that the ruling Communist Party’s first instinct in the event of a market panic was to restrict the ability of investors to act freely.

Xi was forced to defend the government’s handling of the crisis when he addressed business leaders in Seattle, insisting that they had worked, and that the markets had reached what he called “a phase of self-recovery.”

He’s clearly hoping that his visit to the U.S. will spur some recovery in China’s attractiveness to foreign businesses as well.