With European officials huddling this week in an effort to find a way out of the debt crisis threatening to push Greece out of the European currency union, a new working paper from the International Monetary Fund that challenges much of the conventional thinking about how countries that have accumulated substantial sovereign debt ought to prioritize their spending.

First mentioned in a Wall Street Journal piece this morning by David Wessel, who directs the Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy at the Brookings Institution, the paper has an unmistakable message for policymakers in the U.S.: Don’t sweat the debt.

Related: How Government Debt Disinherited the Next Generation

The IMF paper When Should Public Debt Be Reduced? argues that in cases where countries have adequate “fiscal space,” the benefits of paying down public debt outweigh the costs.

There’s a lot to unpack in the idea of fiscal space, but essentially the authors -- Jonathan D. Ostry, Atish R. Ghosh, and Raphael Espinoza -- maintain that if a country is near full employment, can borrow at reasonable (or given today’s climate, historically low) interest rates, and has ample space between its debt limit and its debt-to-GDP ratio, it makes sense not to pay down debt but to let it decline organically as a share of GDP through economic growth.

A country with fiscal space, the authors suggest, is likely to be reasonably well-positioned to take on additional debt in the event of an unexpected crisis. Countries with no room for additional debt, however, could face significant penalties in the event of a crisis requiring more borrowing.

The thinking, according to the authors, is that a deliberate effort to pay down debt would require increasing taxes, which has a distortive effect on an economy by channeling spending away from other uses, like investment in infrastructure.

Related: The Federal Debt Is About to Become a Big Issue Again

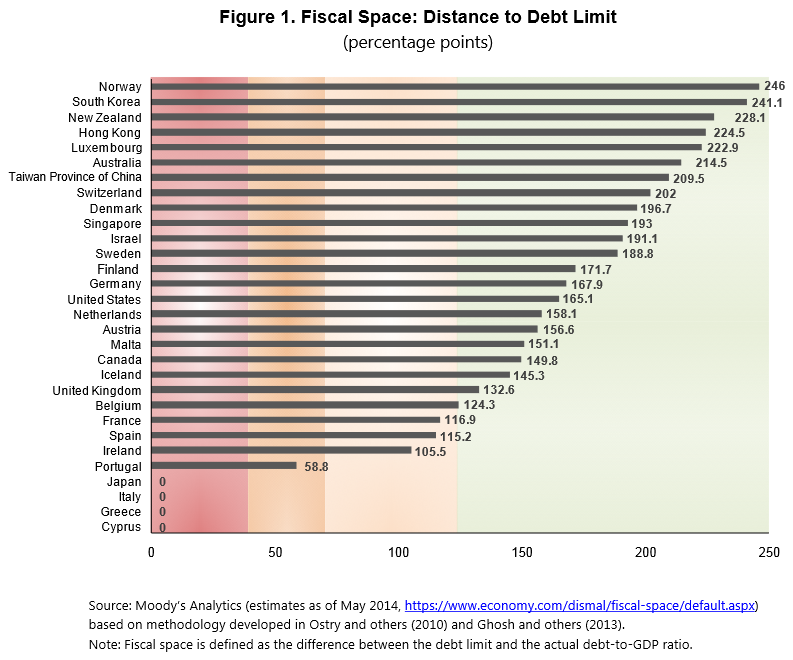

The authors concede that what constitutes adequate fiscal space is a judgment call but offer a general categorization of sovereign debtors with an estimate of just how much room they have. At the bottom, unsurprisingly, are economic basket cases, including Greece, Italy and Cyprus. At the top are Norway, South Korea and New Zealand, all of which have relatively low debt-to-GDP ratios.

The United States comes out with a comfortable cushion, putting it roughly in line with Europe’s economic powerhouse, Germany.

“This isn’t the first time that the IMF has slapped down the austerity crowd. It has, for instance, made the case for borrowing more to finance public infrastructure,” Wessel notes in the Journal.

“Nevertheless,” he adds, “this is an eyebrow-raising moment.”

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times